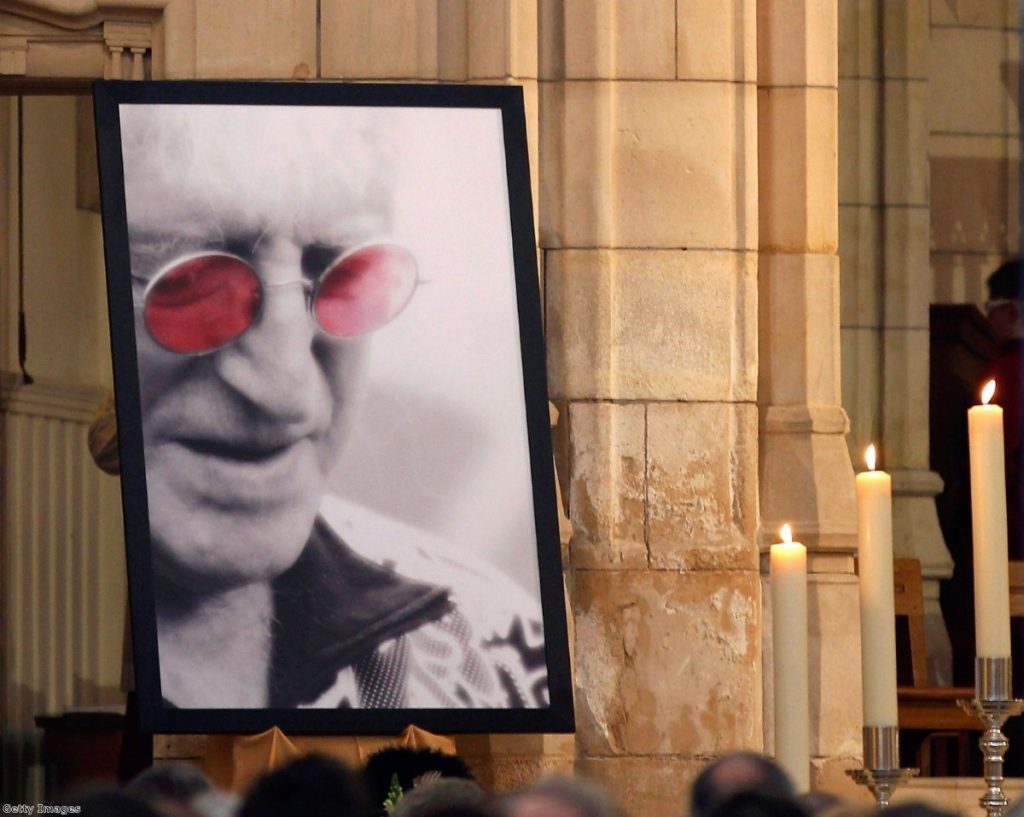

Analysis: How did Jimmy Savile escape justice?

Now the true extent of Jimmy Savile's sexual depravity has been unveiled, serious questions have to be asked about how this disgusting paedophile got away with it.

On autopilot mode, I added 'for so long' to the end of that last sentence. But that's not right, is it? Savile died on October 29th 2011 aged 84, 56 years after committing his first sexual offence in 1955. He got away with it, full stop.

Reading the Metropolitan police/NSPCC report, it seems extraordinary that suspicions about him were not followed up sufficiently while he was still alive.

He defended paedophile Gary Glitter in 2009, as someone who "just watched a few dodgy films and was only vilified because he was a celebrity". Chillingly, he added: "Whether it was right or wrong is up to him as a person."

But Savile was a master of "hiding in plain sight", as the report puts it. He had always insisted Jim'll Fix It was a success because he did not like children – a comment now viewed as a smokescreen by police. His audacity is staggering – but ultimately his arrogance wasn't misplaced.

It could have been different.

As early as the 1980s a female reported she'd been assaulted in Savile's camper-van in a BBC car park. The police couldn't find a file documenting the claim.

In 2003, a victim walked into a West London police station to claim she'd been "touched inappropriately" by Savile on Top Of The Pops in 1973. She was reluctant to proceed unless there were other victims. Because the police had lost the original file, the matter was left to rest.

Three victims made allegations between 2007 and 2009. Although officers from Sussex and Surrey police knew about the other claims, they did not pass this on to the victims, who were reluctant to press a prosecution as a result.

Meanwhile, in 2008, the appalling revelations of the Haut de la Garenne child abuse case on Jersey gripped the headlines. Savile was considered and denied having been there, but photographs later emerged showing him having visited the site.

"I would like to take the opportunity to apologise for the shortcomings in the part played by the CPS in these cases," Keir Starmer, the director of public prosecutions, said in a statement today.

Aside from the shocking details of Savile's crimes, the most appalling revelation today has perhaps come from the report submitted by Starmer's principal legal advisor, Alison Levitt.

Her investigation into the most recent allegations confirms that prosecutions could have been mounted against Savile if the victims had been treated differently.

Instead "errors of judgement by experienced and committed police officers" took place. They didn't give enough weight to the allegations. And, by not telling the victims that they were not alone, they unnecessarily hampered their chances of getting the victims to agree to give evidence.

These mistakes weren't being made because of an improper motive. They were a problem with the system – which, as the DPP acknowledges, means they need to be taken much more seriously.

Starmer says he wants the Savile report to be a "watershed moment" for prosecutors and police officers alike.

The problem remains that in many cases prosecutors are faced with a 'my word against yours' scenario. Allegations made against someone should not be automatically believed, but the risk of being too sceptical has been all too clearly demonstrated by Savile's escape from justice.

Starmer believes there are ways in which the system can be improved. But there is only so much that can be done to change the current system.

The accounts of both the complainant and suspect should always be carefully tested, he recommends. Yet the DPP also thinks it's important that subjecting potential victims to repeated cross-examinations be scaled back in some cases.

Other measures, like allowing those who have already made allegations to repeat them again and improving the way information is shared around the criminal justice system, could help make a difference.

These steps don't feel like a miracle cure, though. The troubling conclusion could be there's no guarantee similar villains won't emerge in the future. Or, even worse, not come to public light at all.

Such pessimism might be a little premature, though. It might seem impossible, but there is a positive side to this terrible tale of abuse.

Since the first revelations about Savile emerged last autumn, the number of victims coming forward has increased dramatically. The National Association for People Abused in Childhood, which received nearly 700 calls in May and June last year, received over 1,300 in October and November. The number of emails it received increased fourfold.

One NSPCC Helpline supervising senior practitioner said: "The whole thing (the Jimmy Savile story) has brought child abuse to the fore, and people are questioning and reassessing the part they can play in protecting children.

"Lots more people who get in touch are now using words like 'duty', 'responsibility' and 'obligation' when we ask them why they are talking to us, and are saying that seeing others speaking out about past abuse has motivated them to take action.

"Seeing people who are adults now talking about how nobody spoke up for them in the past, is a powerful motivator to speak up for children in the present."

It has taken a pervert as monstrous as Jimmy Savile to change British cultural attitudes to child and sexual abuse. Now, at least, the chances are public horror about his activities will make it harder for future paedophiles to achieve what Savile should never have done: get away with it.