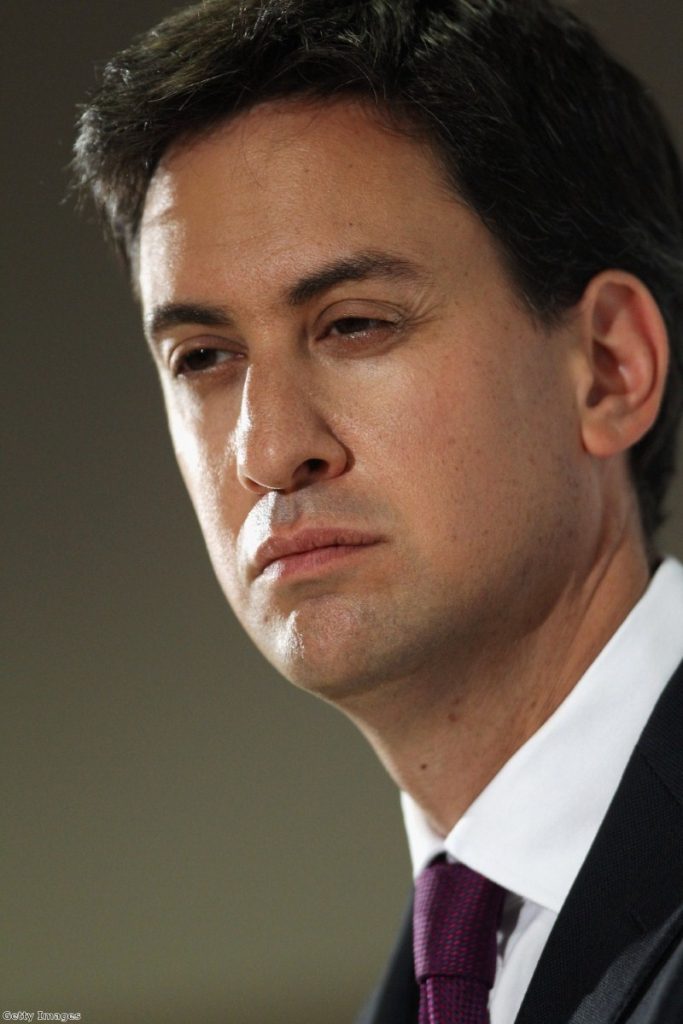

The Week in Politics: The Miliband conundrum

An impenetrable speech and depressing poll ratings leave Miliband in a worse place than where he started.

By Ian Dunt Follow @IanDunt

There's a wealth of advice being offered to Ed Miliband on how to improve his electoral prospects. Around half of it suggests he fundamentally alter his personality. The rest is a cacophony of demands from everyone not happy with the coalition: Go left, go right, sack Ed Balls, become your brother, reject Blair, praise Blair, march with the students, lunch with the bankers, that sort of thing.

The week started badly, with David Miliband visiting conference to a rock star reception before jetting off to the States. How easily he slid over the handshakes and greetings, every inch the Clinton of his era. Of course, that's not really true. David is only marginally less geeky than his brother, but it's in the media's interest to beef up his electability for reasons of drama and storyline. Back when he was a real contender, all the coverage was of him looking absurd with a banana.

To add to his woes, a shattering opinion poll emerged on the first proper day of the conference, showing Labour slipping behind. It was one result from one polling company and therefore possible anomalous, but politicos – including Labour members – seized on it as if they'd stumbled on Merlin's lair. Add in a sprinkling of Twitter celebrity John Prescott hammering his shadow Cabinet, a barely-conceal hatred from most of the media and recurring jokes about his centrist nose, and Ed had reasons to be fearful.

The fratricide candidate started the conference with a pledge to take on the powerful and vested interests. He also made something less than a policy when he promised to get tuition fees down to £6,000 a year. Bafflingly, he announced it without a firm line on whether it would make it into the manifesto. The core message was this: after the financial and expenses crises, phone-hacking and the riots, Britain needed a return to morality – both at the top (asset strippers) and the bottom (welfare junkies). The public are undeniably eager for non-right/left politics but the trouble with navigating these waters is that you can irritate everyone.

And so it came to pass. Ed's badly received conference speech, considered somewhere between impenetrable and irritating by most observers, angered the business lobby by dividing companies into goodies and baddies, while irritating the left by signing up to coalition policies on welfare. It was also quite, quite mad, jumping from point to point with a rhetorical string that appeared more brutalised by the moment.

By the next day, Labour MPs were as unconvinced by their leader as they were before phone-hacking while a much-hyped public Q&A event provided yet more material for his critics to comment on how odd he is. The week ended with rumours of a front-bench reshuffle – something made possible by changes he implemented earlier to the Labour constitution. If anything, the Labour leader ended the week in a worse position to how he started it. Thankfully for him, no-one really cares about conferences so they didn't notice.

Elsewhere in Liverpool, Ed Balls tried to create some political space for Labour to express an economic opinion. The reception at the time was lukewarm, but it appeared better in hindsight, with his five point plans comparing favourably with the vagueness emitted by his party leader.

Harriet Harman irritated all men and most women by holding a gender-specific meeting at the start of the conference. She ended the session with a much less irritating attack on changes to the electoral register which will almost certainly see thousands of disadvantaged and ethnic minority voters fall off the list.

Next week: the Conservatives, in which the usual existential crisis will continue, but with added bravado.