Review: Beijing Coma

This magnificent work of fiction about the Tiananmen Square massacre is destined to become a modern classic.

Beijing Coma – Ma Jian

Vintage – May 7th 2009

Review by Jonathan Moore

There can be a tendency when confronted with the horrors of the world to feel a sense of sympathy for the victims without ever upgrading that emotion to empathy. While we are all suitably shocked by the behaviour of rogue governments and their incomprehensible lack of concern for human life, it’s often far to easy to turn off the news report or finish reading the magazine article and let the matter slip from your mind.

Through our Western eyes, we’re shocked and appalled by the behaviour of our politicians when they use their parliamentary privilege to pay off their mortgage and we’re disgusted and outraged at the very thought of our soldiers, in a warzone, using excessive interrogation techniques on a suspected terrorist. But the concept of our government sanctioning the mass murder and torture of hundreds of our own citizens is entirely alien to us.

It’s for this reason that novels like Beijing Coma are so important to our understanding of the wider world. Through the topic and tone of novels like this, our eyes are able to see into a world that if it were written as pure fiction we would find fanciful, excessively violent and beyond the comprehension of any right-thinking individual.

The story focuses on Dai Wei, a young Beijing student, and the parallel paths of events in his life leading up to and moving on from the Tiananmen Square Massacre of 1989.

Half of the narrative focuses on his experiences growing up as the disgraced son of a confirmed ‘rightist’ in Cultural Revolution-era China. Ma Jian carefully builds up a picture of the overwhelming pressure on citizens trapped under a totalitarian regime. Reading the novel you get a sense that the Chinese government took Orwell’s 1984 and used it as a ‘how to’ guide to create a dystopian society in the real world. This is exemplified in young Dai Wei’s early life when he is interrogated and beaten by the police before being made to write a self-criticism detailing every misdeed he’d ever done, implicating everyone he knew and all the criminal behaviour they indulged in as well.

This part of the novel follows Dai Wei through his life, and loves, in going to university and becoming involved in the student movement that will eventually lead to the protests in Tiananmen Square. There are some truly powerful passages, most notably when he’s reading his father’s diaries about his 20 years spent in a reform-through-labour camp and the horrors of the Cultural Revolution, some of which are genuinely shocking.

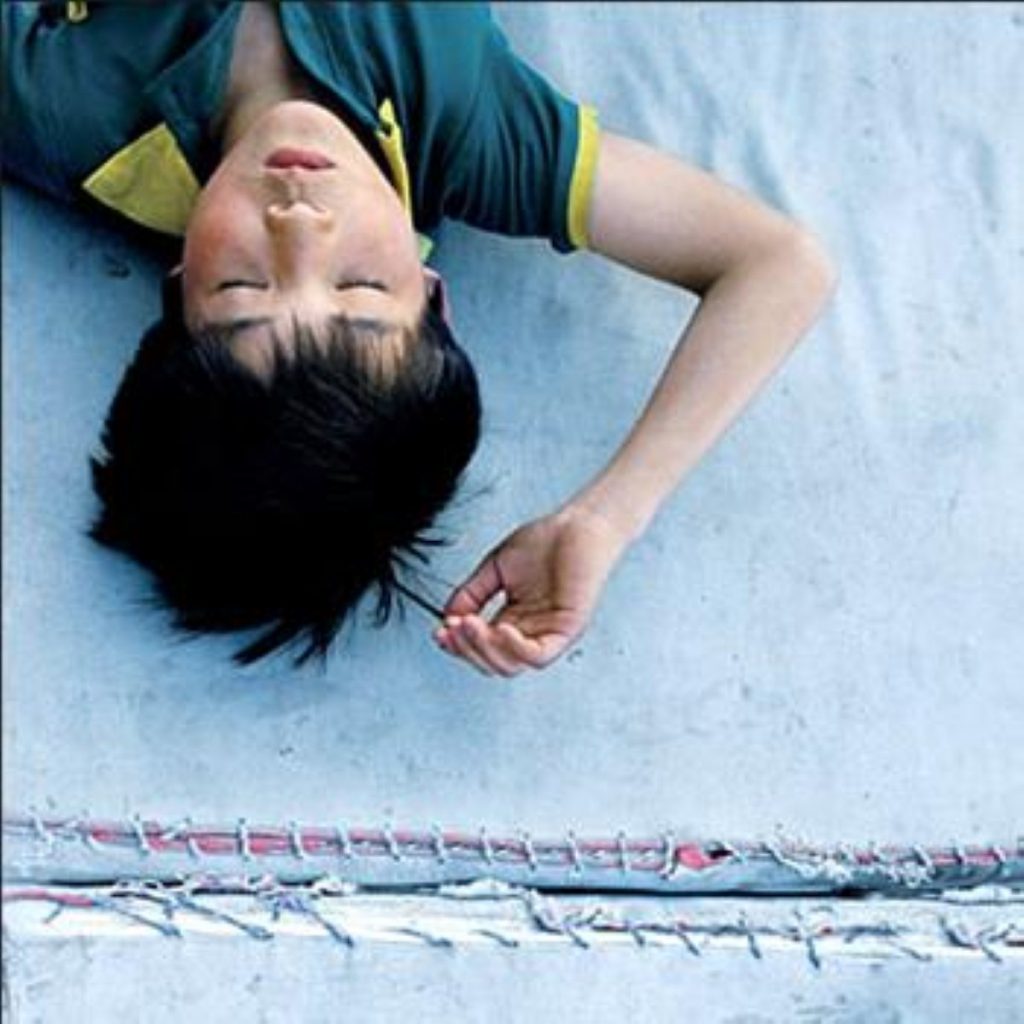

The story of Dai Wei the student is intertwined throughout with the story of Dai Wei and his experiences suffering the eponymous coma. Having survived being shot in the head during the Tiananmen protests he’s forced to live his life entirely within his own mind, able to absorb his immediate surroundings but completely unable to interact with them.

He experiences life following the events of June 4 1989 and hears through the conversations of those around him about the developing nature of China’s economic growth and improving relations with the wider world.

While this part of the story helps to fill out the intervening years between the protests and the present it can often drag and detract from the power of the novel as a whole. Though there are important elements and parallels drawn between events prior to and following the massacre, more often than not the coma sections slow the pace of the novel down and are filled with needlessly whimsical themes.

In what is a fairly weighty novel anyway – in both subject matter and sheer volume – there’s an argument the story should’ve just focused on the student protests. The language, pace, dark humour and engaging themes of those parts of the story are breathtaking as they draw you into a world where confusion reigns and events move beyond the control of those who think they’re in control. Although the message of the coma portions is self-evidently important to the story it’s less clear whether the literary value of them justified their inclusion.

That being said, Beijing Coma is a truly magnificent work of fiction that is destined to become a modern classic. Almost as commendable as the work itself is the unbelievable translation which flows and uses language in such a way that if I didn’t know it was originally written in Chinese I would’ve believed the author wrote it in English.

This is a thoroughly enjoyable and fascinating read, first and foremost. But like great novels it goes far beyond that and provides a message that will affect you on an emotional and political level. The personal and tragic suffering of a people is always a terrible story and through his work Ma Jian cleverly paints a personal picture of the pain of his characters. On a larger scale it’s shocking to think that as we hail China as the world’s next superpower it’s been a mere twenty years since those tragic events occurred. It’s equally shocking that as the world seeks to embrace this new economic heavyweight, the whole story of what happened that day is still not fully known, especially to the Chinese people.

As Ma Jian himself says, for the Chinese “remembering has become a crime”.