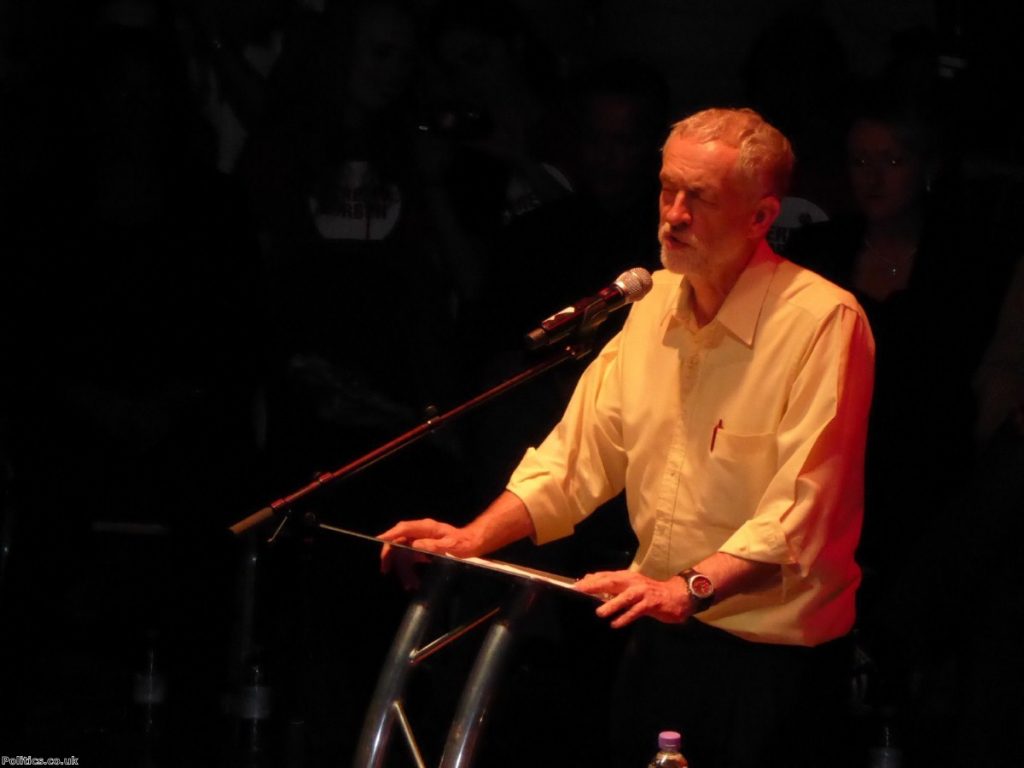

New Labour control-freakery created the need for Jeremy Corbyn

By Alex Feis-Bryce

The majority of grassroots Labour members are euphoric at Jeremy Corbyn's victory. They believe it can bring about a new era for the Labour party and British politics, where substance, conviction and ethical governance replace the Murdoch-fearing populism.

On the other hand, the majority of Labour MPs and commentators in the media, essentially those inside the Westminster bubble, are predicting electoral disaster and the potential death of the UK’s only real opposition to Tory government.

As a former Labour party advisor and parliamentary candidate I was well-schooled in the two fundamental principles of New Labour: that the object of a political party is to be elected and that the only way to achieve that is by occupying the ideological centre ground. It’s difficult to argue with the logic or the electoral maths. However, we must expect more from our political parties than merely gaining power and holding on to it in order to keep out a worse alternative.

Academics talk about political leaders as either preference-shaping or preference-accommodating. The most electorally successful leaders, like Margaret Thatcher and Tony Blair, do both. Voters want political leaders who think like they do, but also inspire them with a vision.

In the last two Labour leadership elections, most of the candidates were obsessed with clinging to the crowded middle-ground. They went further than preference-accommodating and adopted a strategy of preference-mirroring – simply picking policies which they thought made them appear electable. They misunderstood the basis for New Labour’s early electoral successes: a combination of both accommodating the views of voters and showing leadership in developing policies.

New Labour’s key architects were first elected in 1983, when the party had suffered a humiliating electoral defeat after fighting on a left-wing platform. This experience of trauma instilled at the very heart of New Labour a profound fear of being seen as too left-wing or unelectable. It became an electioneering machine founded on absolute media-cycle control. This meant that after a successful first term in power, the party failed to change with the electorate and never managed to escape from its obsession with projecting an 'electable' image.

Uninspiring, managerial MPs who were seen as safe and would stay on-message were promoted and policy was left to insular policy units (comprised of young, white, middle-class predominantly Oxbridge educated policy wonks) and special advisors in Number 10 and the Treasury. This stifled ideas and marginalised original thinkers and experts. A chasm between party activists and the leadership developed.

The language of New Labour, which was once punchy and informal, became tired and jargonistic, more Thick of It than The West Wing. It was worrying when, during the last general election, the Conservatives, led by an Eton-educated millionaire, managed to do a better job of speaking human and sounding as if they’re in touch with ordinary people than the Labour front-bench. While Cameron used simple metaphors such as accusing the last government of "maxing out the nation’s credit card", Labour opted for meaningless slogans like the "squeezed middle" and the toe-curlingly-awful attempt to steal the Tories’ 'One Nation' label.

Blair’s legacy in changing the Labour party led to the dearth of ideas and individual talent which paved the way for Jeremy Corbyn. In that sense, New Labour is responsible for the rise of Jeremy Corbyn.

Since Corbyn’s victory, the focus has been on whether or not he is electable and senior Labour figures, many of whom were involved in the previous two unsuccessful Labour election campaigns, are already dismissing his chances. Those still clinging to the New Labour narrative are crippled by the fear that they could be presented by the right wing press as unelectable and, for that reason alone, the development of a new vision for the party has been stifled. If nothing else, Corbyn’s victory will help the party move on from the past and focus not on how we appear to Middle England but on what vision we have for the future.

It is impossible to say at this stage whether Corbyn will be able to win over enough voters to win an election but that isn’t the only question we should be asking. Would the party's fortunes have improved if we were led by a New Labour clone reading from the same script that worked a decade ago? Should we seek to do more to inspire the electorate than merely second guessing what they want, repackaging it in chrome and presenting it back to them?

To those on the inside who still feel that the party had a vision that resonated with voters, I suggest you take a few years out of the Westminster bubble. I did and the stagnation, paralysis and dearth of ideas in the party became clear. Watching Corbyn’s fellow candidates speak was like watching robots pretending to be human. Much like our slogans before the last election, their language had been through so many focus groups it had lost all meaning. It was as if someone had accidentally sent a text message of New Labour slogans circa-2000 to a landline and played it from their voicemail.

The Labour party was created to change society and create a fairer Britain. We did that in 1945 and 1997 and the real electoral test for Corbyn will be whether he can sufficiently combine preference-accommodating with preference-shaping to carve out a new vision which captures the imagination of the wider electorate.

Corbyn may not win a general election but, unlike his fellow leadership contenders, he will drag the party beyond the factionalism, control-freakery and inauthenticity which still remain from the New Labour era.

Alex Feis-Bryce is chief executive of the multi-award winning National Ugly Mugs charity. Prior to his current role, he worked as a senior researcher and adviser in the House of Commons for seven years and has been involved in a number of election campaigns. He is a former Labour party parliamentary candidate, a postgraduate research criminologist at Northumbria University and a published writer. He was runner-up in 2014 Social Change Awards as 'influencer'. All the views expressed here are his own.

The opinions in Politics.co.uk's Comment and Analysis section are those of the author and are no reflection of the views of the website or its owners.