By Toby Slater

You need a very specific set of interests and experiences to find yourself in a lab in Cardiff at nine in the morning, being injected intravenously with pharmaceutical-grade LSD.

I've been fascinated by psychedelics for many years. I was always interested by the way indigenous tribes used them and in particular the lab experiments with LSD in the years between its invention and the ban. After a while I started swapping emails with Amanda Feilding at the Beckley Foundation think tank into psychedelics. A few freelance writing opportunities led to the opportunity to be screened for an LSD trial.

The results were released this week, to huge press coverage. These are the first ever scans of a brain on LSD. They have significant things to say about therapy and the nature of human consciousness. But for me, this wasn't a dispassionate scientific study. It was one of the most intense experiences of my life.

When you’re injected with LSD, the effect comes very quickly. Almost immediately, my experience of reality began to alter. Lights shone with other-worldly luminescence and my thought process became increasingly fluid. The walls of the preparation room looked like a fresh oil painting.

Trial organiser and neuroscientist Dr Robin Carhart-Harris asked me to sign some papers.

I viewed this activity like an individual from a remote tribe who wasn't familiar with such customs. Even physically signing my name was challenging. The pen felt rubbery and bendy, the table uneven and the papers' surface like water. The ink seemed to glide as smooth as velvet. I found it funny that the pen somehow knew what to say.

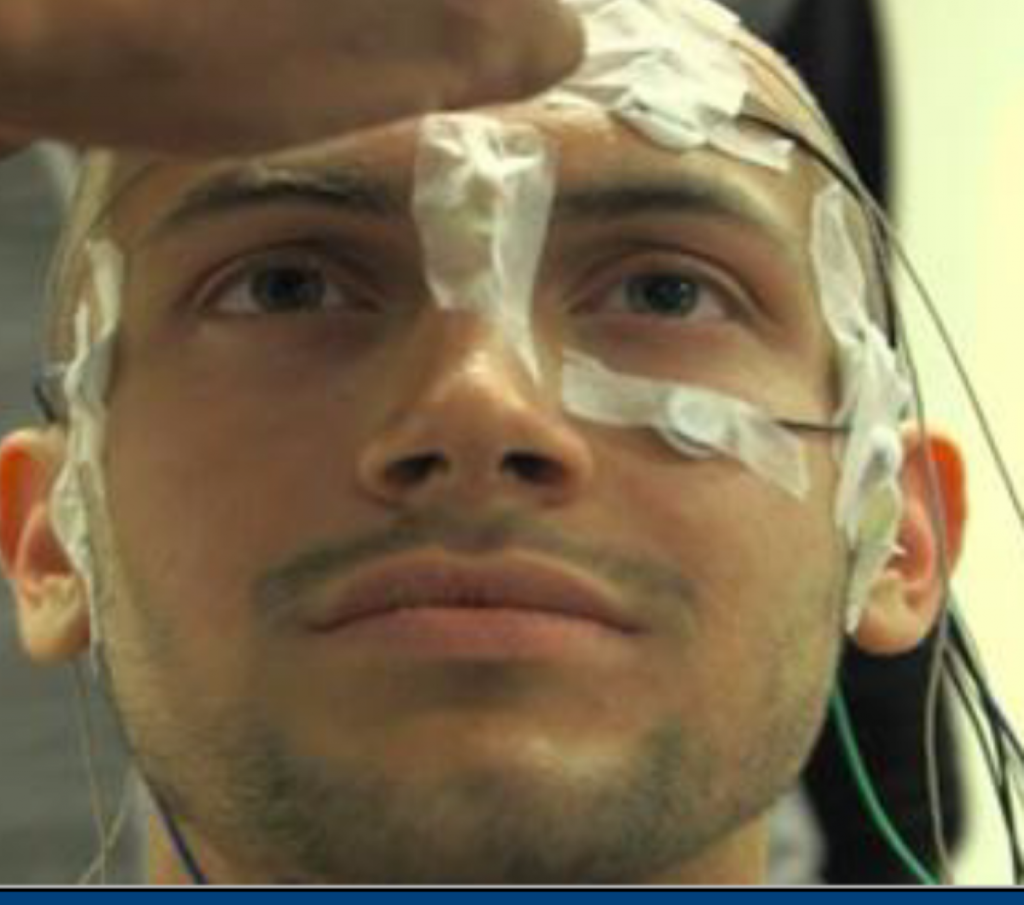

A Dutch PhD student working on the study came into the room to fit some light beads to my face for the scanning process. His 'Dutchness' was strikingly apparent, as was the interaction between him and Robin, who by contrast seemed quintessentially English.

For a while I experienced a state of ecstasy, although I must have looked a little odd, dressed in medical scrubs and with various wires and attachments hanging off me. I was led down carpeted corridors which shimmered like a kind of frogspawn.

But when I got into the scan room, the mood shifted. There was a sinister rhythmic hiss. I later realised this was the energy source of the MRI machine, but it gave me a cold and ominous sensation. I lay on the gurney with medical practitioners leaning over me. It felt like an archetypal death-bed scene.

They reassured me about what was happening and then I was slowly fed into the metallic tube. My head was secured. I was given a heart monitor, a panic squeeze-ball and a control panel to grade my experience. I started thinking about how we crave the unfamiliar, but then, when we get it, our first instinct is often to return to something safe. I tried to reassure myself that, like travelling, the exotic would soon become manageable and enriching.

I felt myself venture beyond the normal parameters of space and time. Vast landscapes and panoramic vistas opened up within me. I glimpsed the arc of my life in its various stages with tremendous clarity.

I could see this terrain and beneath the surface of it was my entire life story. At first I was flying over it, like a kite. But then I broke out of that limiting view-point. This experience could be the ultimate liberation, but from within the isolating MRI scanner it felt unsafe, as if the kite's mooring was becoming perilously fragile. I knew from the literature that this was the beginning of 'ego-dissolution'. I told myself I understood this, yet my understanding was from an ego-bound grasp of reality. In the scanner, subject and object had become indistinguishable. The self-aware 'I' that cognitively understood these things had become obsolete.

The voice of the scan operator asked me to open my eyes and I was shocked to realise the close confines of my environment. I was asked to scale my experience. After the process was completed the screen above my head told me to shut my eyes again. I was frightened to re-enter the inner world alone again. I fleetingly remembered something from my personal life, but having my brain 'photographed' as it happened made it feel as if everyone in the world knew about it, and that then triggered an intensely paranoid feeling. I wanted to discuss it, but I couldn't because I was isolated in the machine. In a normal therapeutic context, this would have been a good moment for a chat, but that wasn't possible here.

I had a vivid recollection of a reoccurring childhood nightmare where I would find myself on the brink of a precipice looking across a giant chessboard. As a child I would look out at this endless black and white vista knowing that I had to make a move which would have everlasting consequences. That distant dreamscape from childhood suddenly became available to me once again. I heard the voices of teachers, family members, old friends I'd lost touch with, and also a kind of archetypal authorial voice – perhaps a projection of my own inner voice interjecting and interpreting.

Then I simply dissolved. I became an oceanic mass of space, an infinite and free-flowing source of energy without divides or means of categorisation. Past and present collapsed. It was completely overwhelming. I felt lost and adrift in the eternity of time.

If you were in a safe and comfortable setting, with a trained guide, this experience could be one of ecstatic liberation. But because I was a volunteer in a brain-imaging trial with people I didn't know, my experience transitioned from dream to nightmare.

My ego was trying to cling on. After all, that's what it does. It creates narrative order and meaning out of sensory chaos. While I fully appreciated and respected the rigours of the clinical trial, it's actually very difficult to let go when you're constantly being interrupted to grade the experience you're having. The tension became unbearable and I pressed the panic squeeze-ball.

Emerging from the narrow tube made me feel like an overexposed film being pulled from a camera. I removed various electrodes and wires and for a while I was just lost in a bewildering matrix of narratives – past, present and future. I was desperately trying to figure out my place in time and how I could get back to the ordinary world of the present tense. Looking back on it, I think perhaps that a sense of time is intrinsic to a sense of self.

It was like trying to complete a puzzle, but there was a missing piece and that missing piece was me.

After a while, I calmed down and returned to a more manageable ego-state where I could begin processing what had occurred.

How does one square this bizarre and challenging experience with a positive therapeutic application? Well, firstly – this wasn't therapy. It was a scientific experiment, and it turns out that that's a context I'm not suited to. But the difficulties – which you could characterise as a 'bad trip'- are exactly what could be seized on and used for positive development if you were a well prepared patient in a therapeutic environment with a skilled practitioner. This is how LSD used to be treated in the years after it was invented, before it escaped the lab and became misused and misunderstood.

Take end-of-life anxieties, for example. A lot of people are frightened of dying because they see it as the end. On psychedelics, the experience of ego dissolution is as if you have died. You can experience the sense of existing beyond the body. That experience can give people a sense of renewed perspective, of being part of the cycle of life. Early research seems to bear this out. A small 2014 study in Switzerland had some very positive results. We may be able to achieve similar results with depression, anxiety and other psychological conditions. LSD can temporarily de-programme social conditioning and open up all sorts of possibilities.

The next day I felt a wonderful after-glow. My ordinary reality seemed brighter, clearer, more vibrant and precious. I felt reinvigorated and intensely receptive to the external world. I savoured the fresh scent of summer grass and took particular notice of the complex design of leaves with their symmetrical contours and veined structures. The efficient exoskeletons of insects enthralled and amazed me. I was drawn to the yellow roses in my garden, which were in full bloom. I felt like a significant part of nature, rather than presiding over it as a separate entity.

The psychedelic state is a return to a primary state of consciousness, like that of a child. Experiencing that in adulthood can be revitalising. It can restore wonder to someone who has lost theirs in a depressive fug of ennui. The science which has come from this experiment has been jaw dropping. But for me, it was an intensely personal experience. It was scary, but also full of wonder.

Toby is a part-time writer of fiction, poetry, music and freelance articles, with particular interests in creativity and the nature of consciousness.

The opinions in politics.co.uk's Comment and Analysis section are those of the author and are no reflection of the views of the website or its owners.