By Kevin Meagher

What would Martin McGuinness have done with his life if fate had not put him on the path it did?

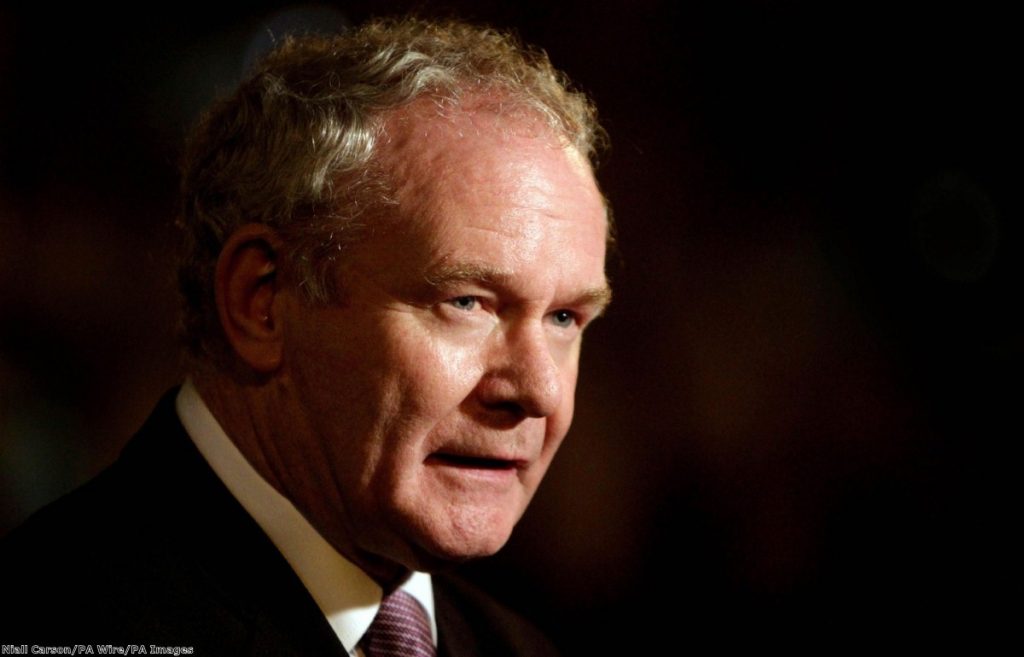

A man of cool judgment as well as fierce determination and personal discipline, McGuinness could have succeeded in any walk of life. A British commander once observed that he was "first rate" officer material.

If he had grown-up in Manchester, or Dublin, he would have made an excellent MP for the Labour party, or TD for Fianna Fail. But McGuinness was born into poverty and discrimination in the Bogside area of Derry.

This was during the dismal years of corrupt Unionist ascendency at Stormont. Options for working-class Catholic lads like him were limited. Unionist moderates, like Terence O'Neill, were denounced and dragged down by hardliners on their own side, for urging reform. Power and opportunity rested in the hands of one community at the expense of the other. And it was staying that way.

What went on in Northern Ireland, stayed there.

Sectarianism was allowed to run rampant. If you didn't own property, you couldn't vote in local elections. In any case, boundaries were rigged to lock in Protestant-Unionist dominance. For many unionists (not all, by any means), Catholics were simply inferior – politically and spiritually. This wasn't just about politics, it was something innate.

Unless this context is borne in mind, it is impossible to understand the decisions Martin McGuinness took with his life.

"If you've got nothing, you've got nothing to lose," sang Bob Dylan. Working-class Catholics had assumed second-class status was their lot until the civil rights movement raised their gaze, awakening both their anger and optimism. But things didn't need to be like this.

McGuinness was not from a particularly political family. Sure enough, events made him so. The defeat of the civil rights protestors – literally bludgeoned off the streets by the sectarian police – saw the advantage default to the 'physical force' tradition, a pattern that has repeated itself in Irish politics time and again.

What followed is familiar enough. McGuinness, the IRA commander, was clinical and determined in waging guerrilla war. Derry looked as though "it had been bombed from the air" by the time he had finished, as one mordant description memorably had it.

The grim litany of death and destruction – enthusiastically entered into by the IRA, loyalists and the British state – coursed a bloody path through the 1970s and 1980s.

Everyone has blood on their hands.

Republicans. Loyalists. Ministers. Officials. Soldiers. British and Irish politicians. They all played a part in propping-up the Troubles as political reconciliation was effectively abandoned as a goal. There's culpability for actions taken and not taken on all sides.

The abnormal became normal. Yet the greater guilt should perhaps be reserved for those who let injustice fester and events spiral out of control in the first place. The end result is always, depressingly, the same. Politics gives way to something worse.

McGuinness's subsequent journey – helping lead Irish republicanism from militarism and Marx to democratic agitation and peace-building has defined the past quarter century, since the first IRA ceasefire of 1994. It was a true act of political leadership and one all but his most vindictive opponents will recognise and praise. Gerry Adams supplied the theory, McGuinness the force of reputation.

He desperately wanted power-sharing to succeed and rose to the occasion, respecting those of different views with a disarming generosity of spirit. Willing to reach out with genuine enthusiasm to unionists and Protestant clergy, usually well away from the spotlight in order to avoid accusations of artifice.

For those against the political process he had harsh words, denouncing dissident republicans as "traitors" for trying to upend the progress he had painstakingly helped to embed.

His unlikely rapport with Ian Paisley was utterly genuine, earning them the sobriquet "the Chuckle brothers." He was calm, sincere and authoritative. And, unlike most politicians, when McGuinness promised to deliver, he delivered. He made things happen.

As such, he is impossible to replace. An incalculable loss to Northern Irish politics. A genuine hard man with enduring credibility who could – and did – lead by example. His life is microcosm of events in Northern Ireland these past five decades. A journey from belligerence to reconciliation. From nihilism to optimism.

Martin McGuinness (1970-1994) shows us what happens when politics is allowed to fail.

Martin McGuinness (1994-2017) shows us what happens when it isn't.

Let that be his epitaph.

Kevin Meagher was special adviser to former Labour Northern Ireland secretary, Shaun Woodward. He is author of 'A United Ireland: Why unification is inevitable and how it will come about' published by Biteback