By Priyanka Motaparthy

In late December, two young women fled Burma's Rakhine State for Bangladesh, making a gruelling journey by foot, a smuggler's rickety boat, and rickshaw into an uncertain future. The women, from Burma's long-persecuted Rohingya Muslim minority, had fled terrible violence wracking their community, where Burmese security forces have burned homes, slaughtered villagers, and gang-raped women and girls.

Both women said soldiers had gang-raped them in their hometown of Pyaung Pyit, and both had scars from the attacks. When I met them in early January, one was still moving painfully, limping from the beating she said soldiers had meted out while raping her. But incredibly, what finally compelled them to flee their country was not being gang-raped, but the news that they were being hunted by the Burmese military.

They had spoken to Burma's national investigative commission, led by the country's vice president, which is supposedly examining alleged human rights abuses in Rakhine State. After the commissioners visited Pyaung Pyit, Burmese state television aired footage of them interviewing one of the women, Jamalida, about her rape. The commissioners and their interpreter were combative, forcefully demanding answers to their questions and dismissing the victim's account. Later, the office of Aung San Suu Kyi, the country's de facto head of government, posted screenshots from the interview on its website, alongside the phrase "Fake Rape." Shortly after the interview aired, soldiers came to Pyaung Pyit with screenshots of Jamalida and asked villagers where she was. Fearing for their lives, Jamalida and another woman who had spoken to the commission fled for Bangladesh.

Their case, recently reported by the BBC, shows why the UK and other concerned governments should not place any faith in the investigations launched by the Burmese authorities to look into alleged abuses in Rakhine. A national and a separate state-level commission have both demonstrated beyond any doubt that they are unwilling and unable to conduct an independent and impartial investigation. Indeed, the national commission has flouted international standards for investigating sexual violence in conflict, standards the UK worked for years to develop and promote in several important ways.

For example, any credible investigator knows that people they speak to should do so with informed consent, so they are fully aware of how their interview will be used, and the risks and benefits of speaking out. Both the women I met said they were not told the true purpose of their interviews, and did not understand that the investigators were from a government body.

Likewise, any proper investigator knows that interviews – especially sensitive ones about sexual violence – should never be conducted in public with dozens of people, mostly men, watching. Both women told me their interviews were also videotaped without their permission, and there was no offer to protect their identities.

Finally, serious investigators are schooled in the delicate art of questioning. You should never interrupt interviewees or try to direct the interview. But in the footage aired on Burma's state TV, the interviewer clearly tells Jamalida: "Don’t say that." He uses a bullying tone and cuts her off mid-speech. An interview conducted like this cannot possibly hope to yield complete or accurate accounts.

Human Rights Watch knows a thing or two about investigations. And unlike the Burmese national commission, we – as well as Amnesty International, the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights and other groups with long expertise in this area – all find Rohingya women and girls' accounts of rape to be credible. Earlier this week, Burma's national commission was in the Bangladesh border district of Cox's Bazar, purportedly to investigate further abuses. Again, Rohingya refugees said that interviewers had interrupted them, ignored them, or accused them of lying. Not only do these methods render interviews worthless, but they violate the overarching principle of sexual violence investigations: do no harm.

The UN Human Rights Council in Geneva has just adopted a resolution to create an international fact-finding mission to investigate the atrocities in Rakhine State. It is now crucial that a strong team be appointed, and that Burma cooperate with the mission.

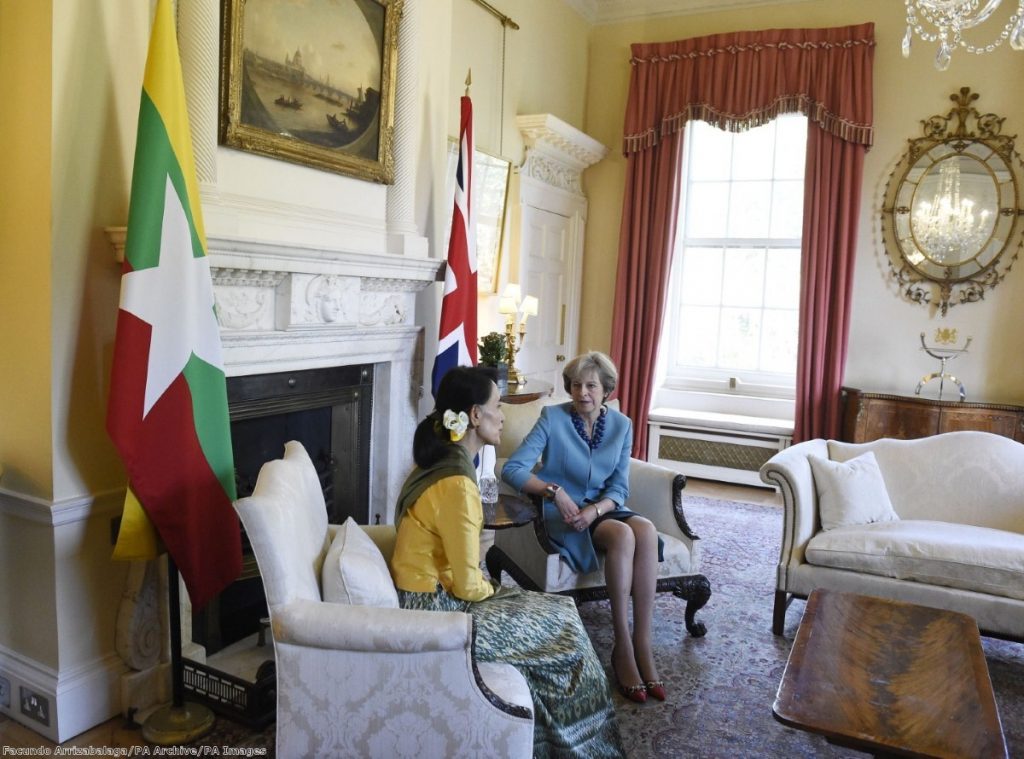

The UK, which has led on important initiatives to combat sexual violence in conflict in recent years, should help ensure that the mission includes experts in sexual and gender-based violence. It should also press Burma to provide unfettered access to investigators, in the hope that those responsible for crimes can be brought to justice. The UK government has done much to champion the rights of those raped in war, and it should not falter now. Rohingya women and girls deserve nothing less.

Priyanka Motaparthy is a senior researcher in the Emergencies division at Human Rights Watch. Follow her on Twitter here.

The opinions in politics.co.uk's Comment and Analysis section are those of the author and are no reflection of the views of the website or its owners.