By Chaminda Jayanetti

The biggest party divide in British politics is not within the Conservatives. Labour's chasm over free movement of people is so vast it is a wonder that either side can even see the other. Just take the following two quotes:

"For years, the elite ignored public disquiet over immigration. It was sidelined because of the net benefit to the economy from EU immigration. Well, the public told the elite where they could stick their 'net benefit'."

"A system of free movement is the best way to protect and advance the interests of all workers, by giving everyone the right to work legally, join a union and stand up to their boss without fear of deportation or destitution."

The first, from former shadow cabinet minister Caroline Flint, was part of a speech last month urging the party to commit to a full-blooded Brexit, outside the single market, customs union, and the realm of free movement of people.

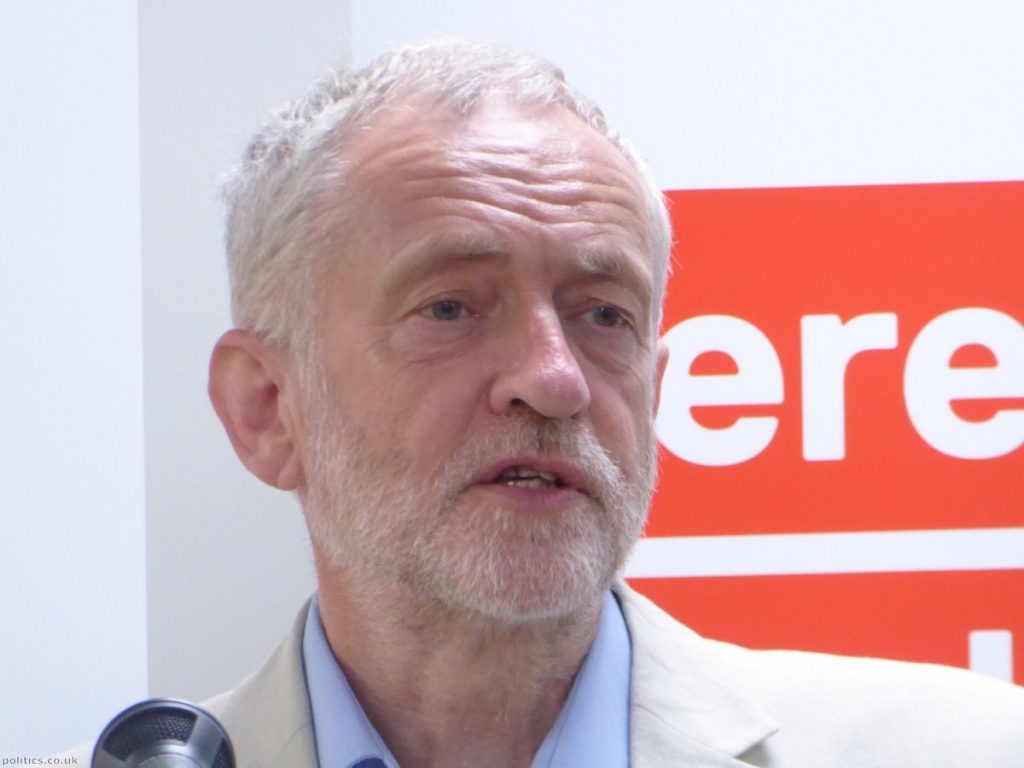

The second is from an open letter calling for Jeremy Corbyn to commit to continued free movement of EU citizens post-Brexit, signed by Labour MPs Clive Lewis, David Lammy and Geraint Davies.

Trying to find a position that unifies these two camps – each representing different worldviews, different economic analyses, and different geographies – is now Corbyn's job, whether he wants it or not.

Labour's 'constructive amibiguity' – or rather, dishonestly facing both ways – during the general election temporarily neutered the Brexit issue, but Corbyn's recent incautiously worded attack on employers exploiting migrant workers has brought an end to the phony peace.

Corbyn's praetorian guard of young, radical left-wingers has suddenly found its voice on free movement.

The line in the sand

Corbyn's long record of defending immigrants gives him a significant 'trust surplus' with what has hitherto resembled a fanbase. After all, Labour's election commitment to end free movement was forced upon him against his will. He seemed distinctly uncomfortable enunciating it during the election.

But the launch early this month of the Labour Campaign for Free Movement is hard to separate from the Labour leader's very different appearance on the Andrew Marr Show in July, where he attacked the exploitation of EU migrants to "destroy conditions" for British workers. High profile supporters reacted with alarm.

It's not that Corbyn's core supporters are enthusiastic Remainers – many regard the EU as a neoliberal project, and most despised its actions during the Eurozone crisis – but the issue they hold dearest is migrant rights. Not just EU migrants, but all migrants – it is common in these circles to regard national borders as a racist concept. Their preferred migration policy would be unfettered global free movement. But EU free movement is a decent place to start.

And while they are not a sizeable chunk of the wider electorate – many genuinely passionate Remainers regard Corbyn with suspicion – they still matter. They occupy senior roles in Momentum. They are his key messengers in the media. They stuck by him during his nadir last summer, when his leadership of the party seemed doomed – indeed, the organisational, campaigning and social media nous of the pro-migrant radical left probably saved him, and certainly boosted his general election performance.

Were Corbyn to maintain his stance of ending free movement of people, divisions could open up in these circles, and enthusiasm may start to ebb away. Any major party leader needs outriders and cheerleaders – and for Corbyn, that means being the principled politician they assumed he was and backing migrant rights.

But in her speech last month, Caroline Flint said the "emotional drive for control" in the EU referendum "was almost totally immigration". How can the Labour leadership square off support for free movement with Flint and other like-minded Northern and Midlands Labour MPs and – critically – branches?

Squaring the circle

Predictions of Labour disaster at the election were based partly on Corbyn's assumed unpopularity, but also on the politics of Brexit. With so many safe Labour seats backing Brexit, it seemed inevitable that Theresa May's belligerent rhetoric would overturn these previously impregnable majorities.

Corbyn's advocates believe Labour's strategy was perfectly pitched to circumvent the Brexit question by focusing on taxing the rich to fund public services. By focusing on the NHS, schools and inequality, the party was able to hold onto its Leave voters while hoovering up Remainers.

To some extent this is true. The British Election Study found that Labour gained more Leave voters from other parties than it lost to the Tories, including 18 percent of 2015 Ukip voters – a proportion that must have been lower in safe Tory seats, but correspondingly higher in the safe Labour heartlands where scooping up Ukip voters was the Tories' entire strategy for success. Using the manifesto and anti-establishment rhetoric to bring out thousands of young voters and previous non-voters in key seats was also critical to Labour's performance.

But this didn't hold true everywhere. Corbynites complained about Labour's headquarters – staffed and run by party centrists – wasting campaign resources trying to defend safe seats. The argument goes that had Labour HQ followed the Momentum approach of piling in to Tory-held targets, the party would have made more gains and Corbyn would now be in power.

It's a tempting narrative but it isn't watertight. Labour lost Mansfield for the first time in nearly a century. They lost Walsall North and North East Derbyshire on big swings, as local Ukip voters flocked to the Tories. Seats in Stoke and Middlesbrough were surrendered. Dudley North and Ashfield almost fell. Penistone and Stocksbridge became a marginal.

These results occurred after the same Labour campaign and manifesto that secured the party a wave of results in the other direction – landing not just Blair-style wins in London and the Remain-voting commuter belt, but also notable gains such as Crewe and Nantwich, Stockton South, Keighley and Peterborough. These latter seats are all decidedly pro-Brexit turf – and while Labour's strategy clearly worked in these constituencies, the party must now try to hold onto them.

The truth is this was the messiest general election in modern British history – uniform national swing went out of the window, with similar nearby seats regularly heading in opposite directions.

But what we do know is this:

- most Leave voters voted Tory

- Labour gained as many Leave voters as it lost

- most Remain voters voted Labour

- most Labour voters didn't vote on the basis of Brexit – only around a fifth of surveyed Labour voters named Brexit as their most important election issue

Marginal gains, marginal losses

Coverage of Labour, the election and Brexit tends to focus on majorities. Most Labour voters voted Remain, therefore Labour should fight against hard Brexit – but Brexit isn't the key issue for most Remain voters, so Labour shouldn't worry about Brexit. It's a line of thinking that can work whichever way you want it to – but each and every way is wrong.

Labour built a broad but fragile and contradictory coalition of voters at the election. It must now add more voters to win next time round. The leadership's strategy is to register and canvas more voters in target seats, banking on increased turnout to flip new marginals that were long thought to be beyond Corbyn's reach.

But in order for that to work, Labour must also hold on to the votes they've already won.

This is why thinking about what 'most' voters want is simplistic. Most Remain voters did indeed vote Labour – but the party was also dependent on Leavers. Most Labour voters didn't prioritise Brexit – but a fifth of them did. Labour would get crushed if it lost either of these minorities from its voting bloc. Even minorities of these minorities could make a difference in tight seats. The margins matter.

Tiptoeing over the tightrope

We don't know when the next election will be. We don't know who will be prime minister by then. We don't know how Brexit will go – though 'badly' seems a good guess – and we don't know how the credit or blame will be doled out by the British public. We don't know if the Tories will pursue their 'one more heave' approach to austerity politics or, alternatively, raise their heads from their porn stash of old Spectators and look outside the window.

Until now, Corbyn and his inner circle had hoped to deal with Brexit by not dealing with it – by obfuscating and doublespeaking while waiting for the Tories to screw it up and take the blame. They did not want to be put on the spot – hence the angry reaction to Chuka Umunna's single market amendment to June's Queen Speech.

The last thing the Labour leadership wants is to say what it actually believes on Brexit – it's hard to say what you believe when you have no beliefs to speak of.

But the foundation of the Labour Campaign for Free Movement makes this harder to maintain. The pro-immigration pressure on the Labour leader from the likes of union boss Manuel Cortes and Momentum activist Michael Chessum – both allies of Corbyn, not his usual Europhile centrist detractors – carries much greater significance than the silly season twitterstorms of ex-Spadocrats in Greek holiday villas.

Matters may come to a head at party conference, with a motion being prepared in support of free movement. Corbyn would no doubt be at ease supporting it, and openly taking on figures like Flint from the right of the party pressing for a tough line on immigration.

But while this would delight his supporters, it also poses new questions. If Labour decides to back free movement, why shouldn't it then back single market membership as well? And won't the Tories cast Labour as the party of mass immigration, shattering Labour's election strategy of neutering the issue by quietly accepting hard Brexit?

On the other hand, if Labour doesn't back free movement, won't the principled leader have betrayed his most fundamental principles? In which case, what is the point of him in the first place?

It is almost as if Corbyn's most favoured outcome would be for him to back free movement but for the party to vote it down.

While Tory splits on Brexit have been caused by genuine (if hopelessly ill-informed) disagreements on the best way forward for Britain, the Labour leadership's mixed signals are the product of cynical positioning in the absence of anything approaching principle.

Corbynites have until now argued that Labour's Brexit stance, including ending free movement, allowed them to shut down the issue on the election doorstep and – in a phrase once beloved of Blairites – earned them 'the right to be heard' on the issues they really wanted to talk about. Primarily, cuts.

But Brexit is a monster that obeys no master. Corbyn has tried to avoid discussing its details. Now others are doing the talking instead. The time for strategic silence is running out.

Chaminda Jayanetti is a freelance journalist. You can follow him on Twitter here.

The opinions in Politics.co.uk's Comment and Analysis section are those of the author and are no reflection of the views of the website or its owners.