"In a way, this is the first time we got an empirical look at what a hallucination is," Amanda Feilding, executive director at the Beckley Foundation, says. She's looking at remarkable new images of brain scans of people on LSD – the first time they've ever been taken anywhere in the world. They seem to show areas associated with visual data lighting up despite the test subjects having their eyes closed. "Images are coming to the sensory cortex without the eyes being open," Feilding adds.

The findings are remarkable, but perhaps not as remarkable as the fact the study is being published at all. To be able to do studies with illicit drugs like LSD is very difficult: the cost of legal access to the drugs is disproportionately expensive – running up to £100,000. The 'schedule one' certificate from the Home Office is hard to secure, grants are difficult to find, and there is a strong political and professional pressure not to dabble in this area.

But Feilding is rather immune to all this. The Countess of Wemyss and March grew up at Beckley Park, a Tudor hunting lodge with three moats just outside Oxford. She developed an early interest in states of consciousness and in 1998 she converted the lodge into a foundation for promoting empirical approaches to drugs.

"I've wanted to do research into the mechanisms underlying LSD – and also psilocybin [the active ingredient in a kind of psychoactive mushroom] and cannabis, since I set up the foundation," she says. "But I was always told by the scientists on my board that I would have no chance of gaining approval to do a study on LSD. Psilocybin was much easier because no-one knew what it was. Poor LSD was the priest of toxicity from the 60s. There's this historic baggage that those three letters – LSD – carry. We know from research that when taken in a safe setting there is no risk to the subject. It is an amazing taboo which has passed through the decades."

Early tests on LSD in the 1950s and 60s seemed to suggest that it could have a useful role in therapy, particularly in the treatment of depression, anxiety and even alcoholism. But after the drug was banned, the studies dried up.

David Nutt and Amanda Fielding. Photo by Robert Funke

One of the people Feilding started working with was professor David Nutt, of Imperial University, whose own experience of clashing with authorities over drug research came to a head in 2009 when he was sacked as chair of the Advisory Council of the Misuse of Drugs for ranking drugs according to the harm they do the user and society. Magic mushrooms were at the bottom. Alcohol was at the top. It was, in reality, the specific job Nutt had been asked to do by the Home Office, but the findings of his analysis were so politically unsayable he was forced out.

"It's the worst censorship of research in the history of humanity," Nutt says of Home Office restrictions on studies of banned substances. "Many scientists are scared that if they work in this field they'll be stigmatised."

However, Nutt and Feilding didn't have much to risk. They were both out and proud as campaigners for a more rational approach to drugs. They conducted a psilocybin study into depression which found some measurable improvement after just two doses of the substance.

For this most recent experiment, test subjects were split into a group taking LSD and a control group. The LSD group was injected with the drug intravenously. They then filled in self-assessment questionnaires and completed a brain imaging programme. The programme included arterial spin labelling, an MRI method to measure blood flow within the brain; resting-state MRI, to assess functional connections within and between brain networks; and MEG, a method to detect brain waves.

The test subjects were made up of people who had tried strong psychedelic drugs before. But all the same, being injected with LSD in a lab in central London and then going through the loud, cramped experience of sitting in an MRI machine would not have been a particularly enjoyable experience. "As I told the subjects, it wouldn't be what I would want to do," Feilding laughs. "But the room is made as welcoming as possible. For the scientific research, I think it's worth it. It is rather magic to combine subjective reports with an insight of what is actually happening in the brain."

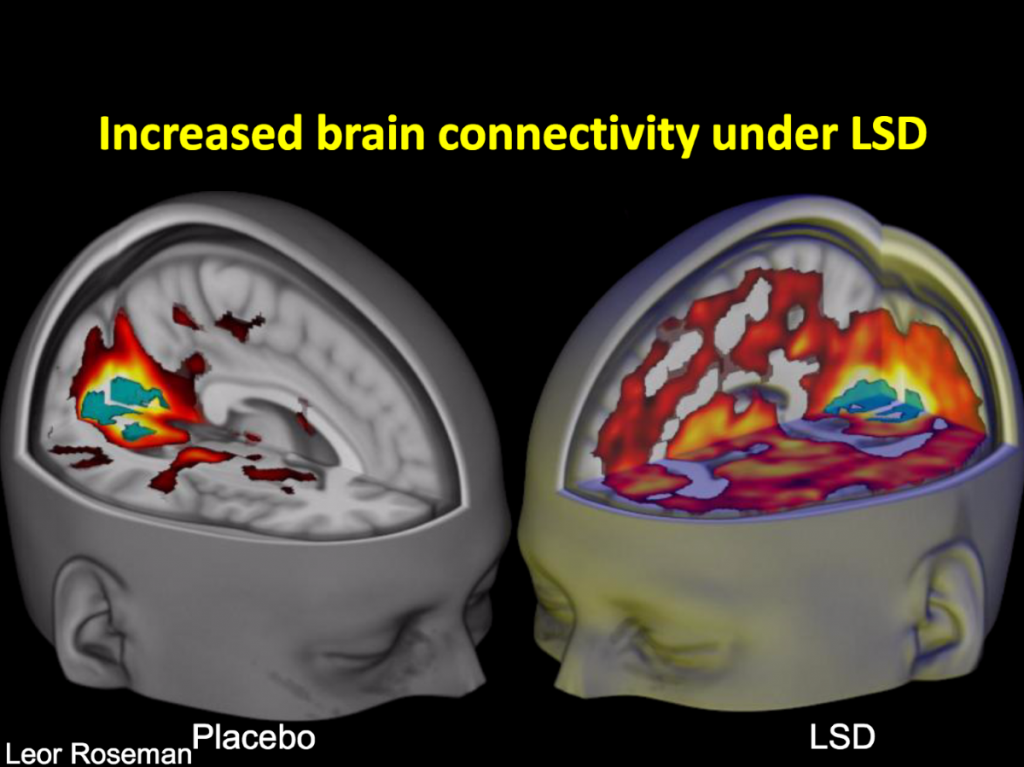

The findings were fascinating. The researchers found that the connectivity of regions involved in vision increased on LSD so that the visual cortex was 'talking to' more of the brain. This, along with changes in brain waves in visual regions and an increased blood flow in that area, correlated with reports of hallucinations. It seems to suggest that hallucinations involve the seeping of visual activity into other areas of the brain.

But something else interesting happened in the test. Researchers found that the 'integrity' of brain networks had started to deteriorate. And the deterioration of integrity in one specific network – the default mode network – correlated with reports of 'ego dissolution' by the test subjects. This suggests that the default mode network could be responsible for our sense of self.

As the trip went on, distinct brain networks became more connected to one another, allowing for wider and more integrated communication.

Quite apart from the obvious psychological and philosophical implications, the findings could potentially open the door to new avenues for therapy. "There's much more 'cross talk' in the brain," Feilding explains. "That appears to have the beneficial effect of shaking rigid patterns of thought which underlie illnesses like depression, anxiety, addiction, obsessive compulsive disorder, etc."

Much of this still needs to be demonstrated more conclusively. The history of psychedelic research includes many serious scientists but also many inflated claims about the benefits of the substances. And there have been one or two cases – one thinks naturally of LSD guru Tim Leary – where the latter was eventually coming from the former.

But the results are startling and certainly suggest a need for further research. Unfortunately, that is hard to do with the current disincentives on using psychedelic drugs in scientific tests.

"That's one of the reasons we've done it," Nutt says. "It's arguably the most interesting drug in the history of humanity and no one has done studies on what it does to the brain, because regulation makes it so difficult. We have to show you can do it and there's value in doing it. Someone has at last worked out what LSD does to the brain."