This week Theresa May experienced her worst political scandal since she became prime minister.

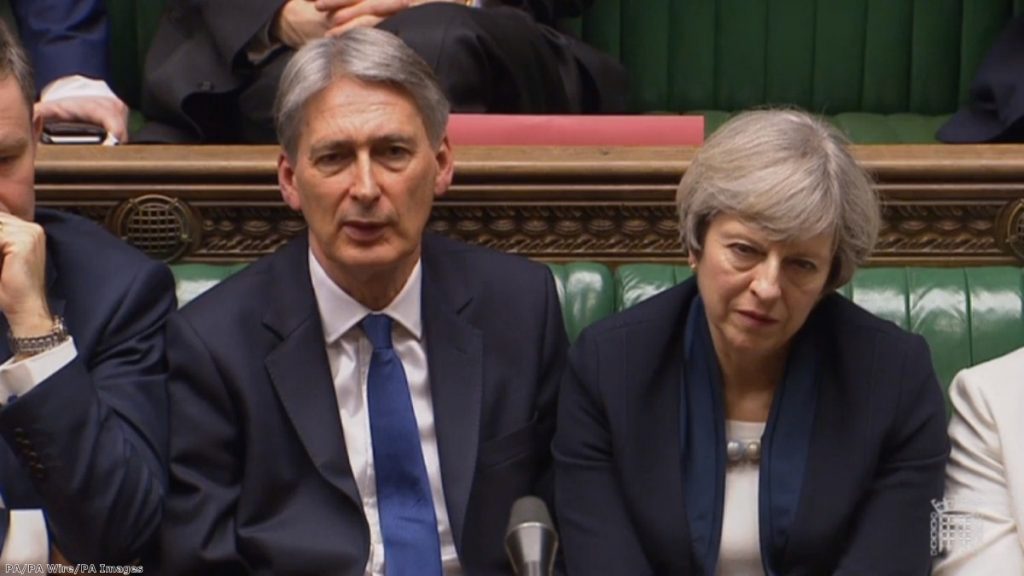

The rage was almost Biblical. Every newspaper splashed on it. The Sun started one of its campaigns. The Telegraph branded it "one of the worst Budget calamities of modern times". Chancellor Philip Hammond joined the special political club of people who are followed everywhere by journalists shouting: "Are you going to resign?"

What had he done? Had he been caught at home with the bodies of murdered taxpayers? Had he burned a poppy? Was he found dressed up like Princess Diana doing an impromptu Sex Pistols gig in Camden? No. He had raised taxes on the self-employed by an average of £240 a year.

From April next year, there'll be a one percent increase in the main rate of Class 4 National Insurance Contributions for the self-employed, with another one per cent increase the year after. The flat-rate Class 2 NICS will be abolished and the tax-free dividend allowance reduced from £5,000 to £2,000. That's the lot.

May looked startled by the strength of the backlash. Plainly she was aware of the policy and had framed it as part of her 'fairness' agenda. She obviously thought that the absence of any functioning opposition in parliament gave her the breathing room to do a quick raid on people who would otherwise be thought of as core Tory supporters. She was wrong. By the time she was responding to the criticism in Brussels on Thursday she'd decided to delay the legislation until the autumn, with every chance that it would be quietly killed off before then.

In the upside-down world of the British press, this was the greatest scandal to rock Downing Street since the prime minister first stepped foot in it. But a few other things happened this week.

The American Chamber of Commerce to the EU, which represents US business interests in Europe, said May's decision to leave the single market could cost the UK 1.4 million jobs and £488 billion of direct investment from US companies in Britain.

The drumbeat of war for a second Scottish independence referendum, largely the result of May's refusal to consider Scottish pleas to stay in the single market, grew deafening. One government minister branding it "inevitable" and said the only uncertainty was about the date. An STV poll put the result on a 50-50 knife edge, a far stronger position for the nationalists than the 32%-38% range they were getting a couple of years ahead of the 2014 campaign.

In the Commons, international trade minister Greg Hands admitted the government was still desperately trying to recruit trade experts, despite the fact that Article 50 talks – the largest trade negotiation this country has ever undertaken – will start before the end of the month. Those it does have seem to be largely from the civil service. They will be going up against an army of specialist trade experts often considered the best in the world.

Under any sane assessment, these are far bigger scandals. The actions of the prime minister have created the greatest threat to the Union it has ever faced. They are so dangerous they threaten millions of jobs and billions of investment. Her preparation has been so abysmal that the government admits it does not have the capacity to adequately negotiate the arrangements which will define Britain's economic future.

But on the other hand, self-employed people will lose £240 a year.

Whether you support or oppose that national insurance change is neither here nor there. What's remarkable is how unhinged the coverage of British politics has become if this is considered the scandal and the other stories just footnotes.

What really matters is whether the press support Brexit and by and large they do. Its dangers are therefore ignored and the decisions made in its honour are praised, regardless of their effectiveness or their repercussions. This has created a black hole where scrutiny should be and a complete lack of proportion in coverage. Seeing the frenzy over a tax change which will bring in £2 billion to the Treasury against the backdrop of largely-ignored cataclysmic economic gamble shows how provincial and myopic British journalism has become.

We are living in an upside-down world where what is small is big and what is big is invisible. Soon enough – possibly even by next week – Article 50 will be triggered. And then the imaginary world will come crashing down, as it meets the brute force of reality.

Ian Dunt is the editor of Politics.co.uk. His book – Brexit: What The Hell Happens Now? – is available now from Canbury Press.

The opinions in politics.co.uk's Comment and Analysis section are those of the author and are no reflection of the views of the website or its owners.