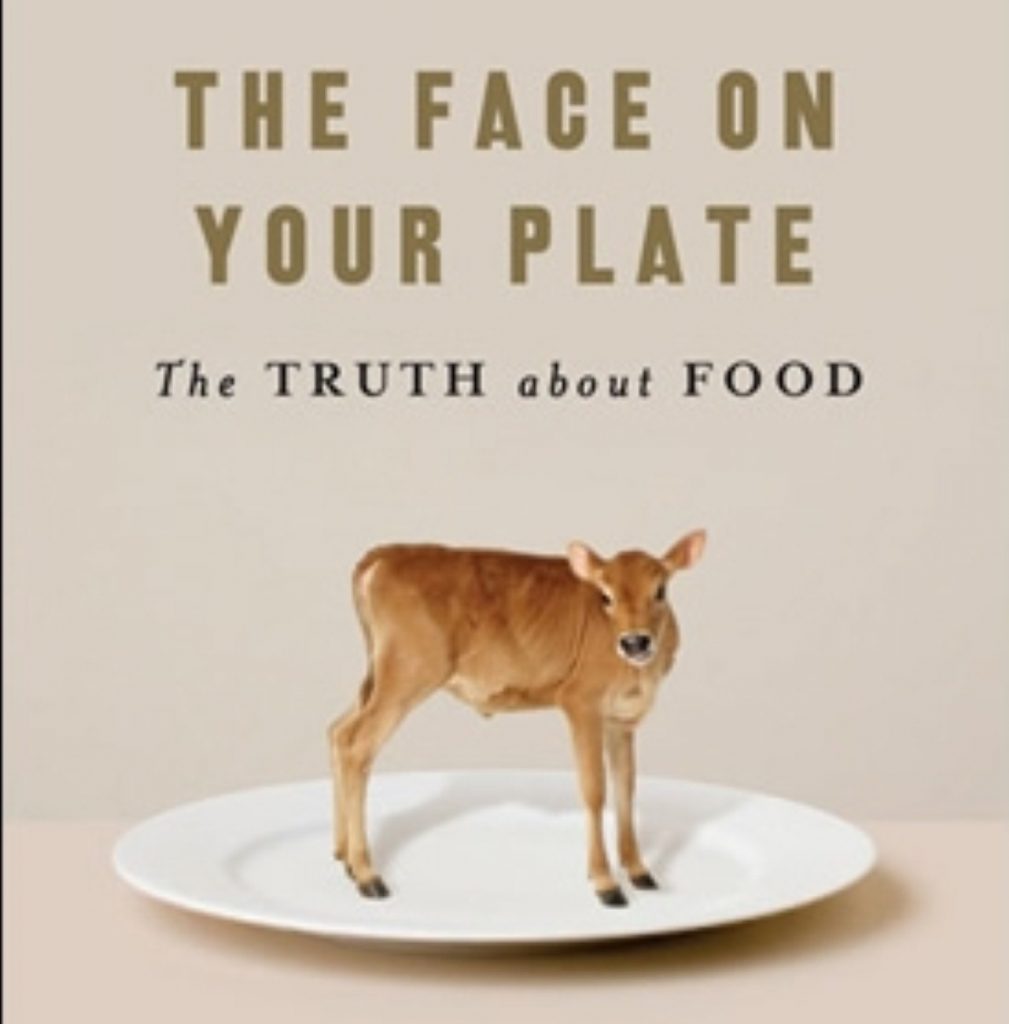

Review: The Face on your Plate

A thoughtful, persuasive text outlining some key reasons for not eating meat, ranging from the personal to the political.

The Face on your Plate: The Truth about Food – Jeffrey Masson

WW Norton & Company – 16 June 2009

Review by David Roberts

In The Face on Your Plate: The Truth about Food, Jeffrey Moussaieff Masson sets out a reasoned argument for why meat and dairy should not be consumed by humans.

American-born Masson first started out as a scholar of Freud and psychoanalysis before publishing a series of books about the emotional life of animals, one of which was the bestseller When Elephants Weep. In his latest short but succinct book, he lays out three central arguments supporting the adoption of a vegan diet: that eating meat is not natural, that livestock and agribusiness is inefficient and damaging the planet, and that the happiness of animals is important. The style is persuasive yet he refrains from brow-beating readers and avoids sensational statements. Masson uses his background in psychoanalysis to try to guide readers towards an epiphany – a “transformative moment” as he puts it – when they identify the food on their plate with sentient creatures and think about the consequences of their dietary decisions from a personal, spiritual and global perspective.

He starts off by challenging the idea that humans are meant to eat meat, suggesting that our teeth, jaws and digestive enzymes are not suited to this sort of diet in the same way that other carnivores are. He suggests that cultural conditioning has led to the prevalence of meat in the modern diet and that it is unnecessary or even harmful to ones health. Masson asserts that human beings can live a perfectly healthy existence without consuming animal products. This part of book could be seen as obvious, given that it is generally accepted that eating more fruit and vegetables is healthier. This section is likely to support the view of those already converted to Masson’s cause, but aspects of it could face scepticism from dedicated meat eaters. However, the fact that a diet without animal products is not unnatural or a just a strange modern lifestyle choice is a simple yet important point.

The author progresses to arguing that animals are conscious entities and the way humans treat them is unnatural. In the vein of writers such as Peter Stringer, Masson challenges the notion that causing pain and suffering for food is acceptable. He suggests that people are culturally detached from the realities of the farming and fishing industries. The way “bacon” is not called “pig” and “veal” is not “baby calf” is cited as evidence of the instinct to put distance between the idea of a living animal and a meal on a plate.

He describes visits to farms where conditions are considered excellent but uses the experiences to illustrate how even in the best conditions, there is inevitable suffering. He notes that female cows are separated from children so that they keep producing milk and that water birds like ducks are kept in confined enclosures. According to Masson, there must be considerable suffering on the animals’ parts because they cannot do what comes naturally and what their instinct tells them to do.

The final part of Masson’s three-pronged attack is to argue that the meat, dairy and other livestock industries are not environmentally sustainable. According to a 2006 United Nations report, “70 per cent of all agricultural land and 30 per cent of the land surface of the planet” is dedicated to producing livestock. Masson’s assertion that meat is a dangerously inefficient way to produce food is difficult to disagree with. He explains that the agribusiness is the single largest contributor to global warming with two-thirds of the methane and three quarters of the nitrous in the atmosphere come from this industry.

Masson’s arguments about the environmental damage being caused by the meat industry could be the most persuasive to those who still love their steaks and hamburgers. While some might be able to brush off ideas that eating meat is an unnatural activity for humans, or continue in denial (Masson’s word) about the pain and misery of farmed animals, the statistics about the environmental damage agribusiness is causing are compelling. However, this is not to suggest that the other thrusts of Masson’s book do not have value.

Even those who do not accept the main arguments about whether eating meat is natural will be likely to concede that at the very least, avoiding animal products is a viable and natural dietary option. His discussion of the suffering experienced by farmed animals tries to bridge the mental gap between living creatures and food. It is in this section that one becomes more aware that this is a book aiming to convert people to a cause. This is because for all the logical reasons there are to adopt a vegan diet, the emotional importance of recognising the value of animals and associating them with meat is crucial for personal conversion. Masson’s final section on the environmental ramifications of agribusiness takes the scale of the argument to global levels. It is not just beneficial to our health and state of mind, reducing meat consumption is vital for our survival.

While The Face on Your Plate: The Truth about Food is a persuasive and essential text for anyone considering a change in diet, it is not perfect. Its logical measured style might fail to sufficiently ignite readers to take action on the book’s contents. However, this could even work in the book’s advantage because it is unlikely to evoke a knee-jerk reaction from meat-eaters reading it. The writer tempers his approach and keeps the book focussed on reasoned arguments rather than launching into moral judgements against those who disagree with it principles.

The latest work from the author of When Elephants Weep: The Emotional Lives of Animals is an absorbing and compelling text that will no doubt be a must-read for vegetarians and vegans alike. However, Masson’s credentials as a psychoanalyst and his logical, tempered writing could see the book finding its way into the hands of many a meat eater. And he might just convert some.