Review: Campaign 2010 by Nicholas Jones

Published by Biteback, 288 pages, £9.99

David Cameron is just as obsessed with the machinations of the British tabloids and broadcasters as New Labour ever was. He’s just better at it.

By Samuel Dale

Documenting Cameron’s rise to the summit of British politics is so straightforward that it becomes, paradoxically, almost unconventional. As the first politician to rise from Tory central office to prime minister, Cameron has been at the heart of British politics since he left university. He learned his trade working on the 1992 election campaign and as political advisor to the chancellor Norman Lamont and home secretary Michael Howard. This was no ordinary introduction to political life. This was the gold-plated fast-track to the very top.

Author Nicholas Jones’ big theme is the relationship between politicians and the media. And it is clear that Cameron is an expert media handler, whether it is speaking without notes for party conference speeches or wooing the News Corporation press. He really seems to hit the PR spot when he is pictured with huskies in the Arctic to symbolise his green credentials.

One of the most fascinating things to observe is just how fickle the national press are and how easy this is to appreciate in a single volume depicting one man’s rise. Cameron’s approach is contrasted with the ‘New Labour spin machine’, particularly over the hug-a-hoodie episode. The phrase was devised from a speech made by Cameron when he said youths wearing hoodies needed some love, not just punishment. The blame is laid at the door of spinners Alastair Campbell and Peter Mandelson. But it is hard to see the difference with Cameron’s approach when he launches a ‘forces manifesto’ to coincide with a Sun newspaper campaign, or by urging his ministers to call Gordon Brown a ‘ditherer’ at every opportunity.

A whole chapter is dedicated to the switching of the Murdoch press from Labour to the Conservatives. Cameron clearly places huge importance on the old Australian tycoon and tried to please him with timely attacks on the BBC and the need for greater diversity in the media. His hiring of former News of the World editor Andy Coulson as director of communications was also, in part, a strategic move to gain an inside track into News Corporation’s workings.

There is criticism for Cameron over his handling of the Lord Ashcroft and Zac Goldsmith non-domicile affairs – from a PR perspective, at least. Jones believes the incident highlights a key Cameron flaw, loyalty to his inner circle. The author contrasts how he had no problem tossing out the Tory old guard during the expenses scandal but hesitates over throwing his old pals Goldsmith and Lord Ashcroft to the dogs. As a result of this misjudgement a ticking bomb is allowed to explode very close to the general election.

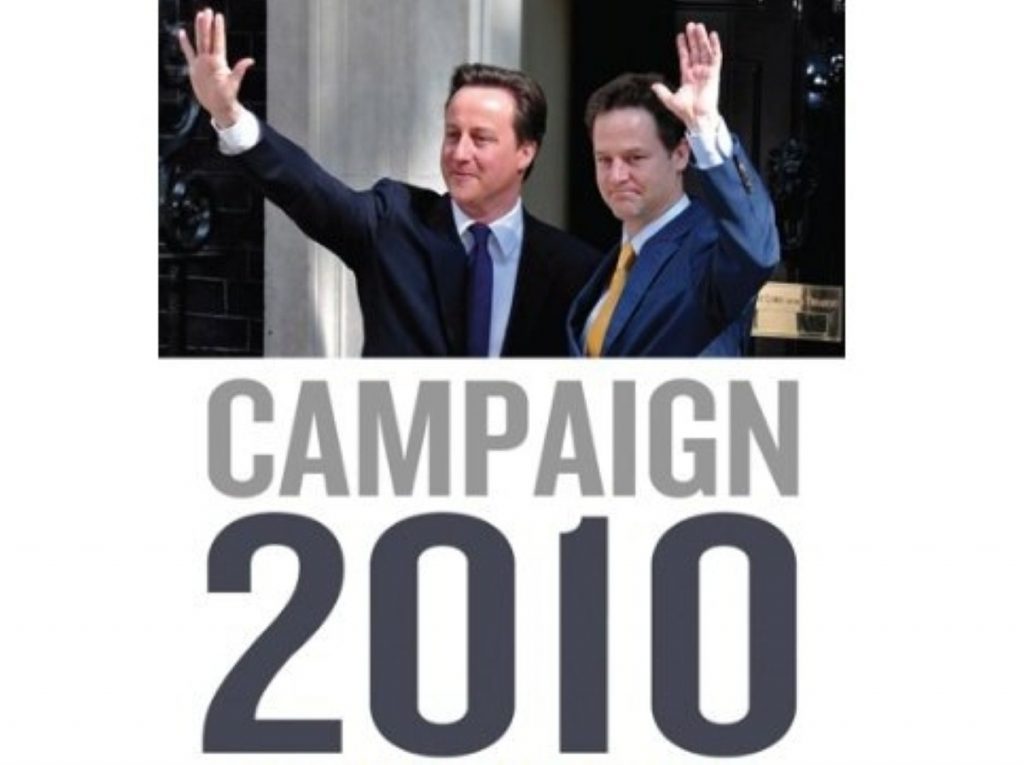

As for the election campaign itself, Jones provides a breathtaking account of one of the most exciting periods in British political history. Cameron’s decision to enter into TV debates and give Nick Clegg equal billing as himself and the former prime minister is dismissed as a misjudgement. It is only after the election result, Jones argues, that Cameron came into his own. And it is hard to disagree that his “big, open and comprehensive” offer to the Liberal Democrats was a masterstroke and his willingness to compromise and work together contrasted with the difficult Brown.

As Jones points out so effectively, the media blackout only served to intensify this drama. Perhaps this is the exception which proves the rule. When the press became less relevant Cameron formed his determination to form a coalition government and reach Downing Street. By joining with the Liberal Democrats he confounded the national press and turned disappointment into opportunity. After years of being obsessed by daily headlines, the only time he ignored the media was perhaps his finest hour.