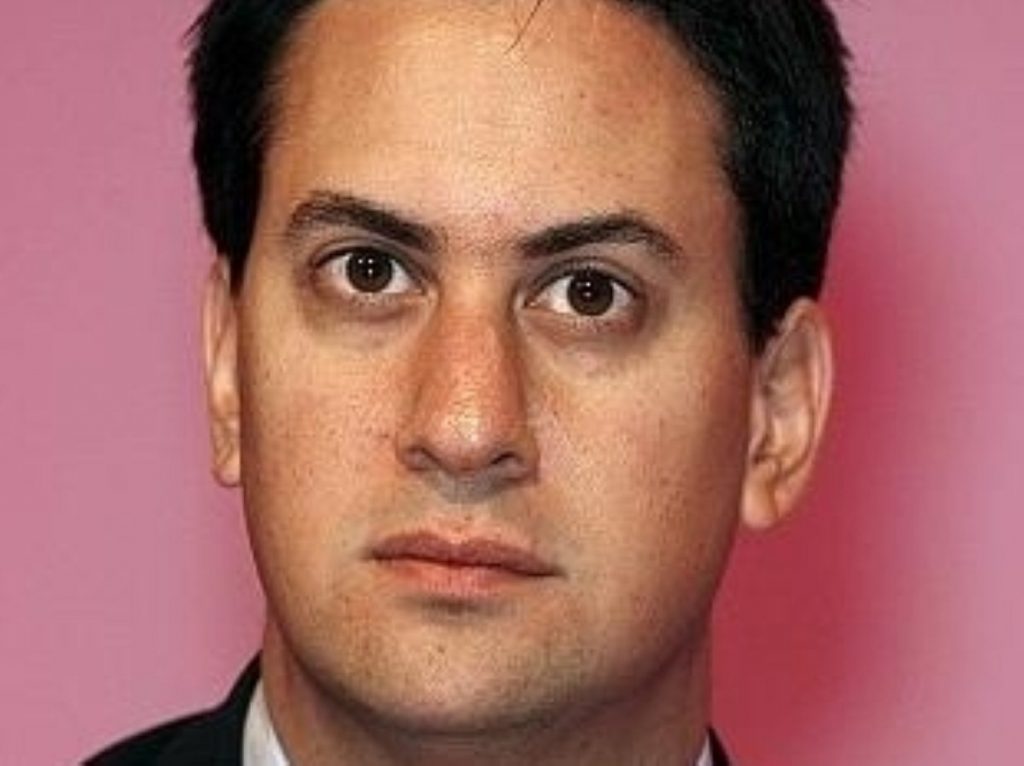

Analysis: Unpicking Ed Miliband’s invitation to Lib Dems

Ed Miliband has published a letter to disaffected Liberal Democrats, calling on them to join Labour. politics.co.uk dissects it.

By Ian Dunt

Ed Miliband has a niche in the market: his ability to drive a wedge between the Liberal Democrats and their coalition partners. He thinks his politics are perfect for our time. Diane Abbott is still too left wing, Ed Balls is too tainted by Brown, David Miliband is too tainted by Blair and Andy Burnham’s anti-metropolitan elite message doesn’t stand up to scrutiny.

The leadership contender is so committed to his agenda, you rarely hear him say a bad word about the Tories. Instead, his fire is concentrated indefinitely on the Liberal Democrat leadership. His first shadow ministerial statement in the Commons after the election, fired off angrily towards Lib Dem energy and climate change secretary Chris Huhne, encouraged Lib Dem MPs to vote against the government. As rumours of Charlie Kennedy’s defection to Labour spread over the weekend, Miliband was busy rolling out the welcome matt to the former party faithful. Finally, his letter in the Guardian today extends that invitation to Lib Dem voters.

“Our society is at risk of being reshaped in ways that will devastate the proud legacy of liberalism. We see a free market philosophy being applied to our schools, wasteful top-down reorganisation of our NHS, and the undermining of our green credentials with cuts to investment. At some point you have to conclude that this is not a mistake here or there, but part of a pattern. The pattern is of a leadership that has sold out and betrayed your traditions, including that of your recent leadership: Steel, Ashdown, Kennedy and Campbell.”

Miliband’s reference to past leaders serves to both encourage reporting of possible defections at the top of the party (among figures known to be uncomfortable) and also to reassure any wavering Liberal voters that they are not betraying their roots. His next task is to show that Labour has changed, despite the short amount of time that has passed since the election and the absence of a new leader.

“I believe I am winning the argument that we must turn the page on New Labour and the mistakes it led us to. For example, the argument is being won that a graduate tax based on income would be fairer than tuition fees and a market in higher education. The argument is being won that on issues like ID cards and stop-and-search we became too casual about the liberties of individuals. And I believe the argument is being conclusively won that we must recognise the profound mistake of the Iraq war.”

This selection of three topics serves as a checklist of Lib Dem pressure points. First graduation tax: students are, in effect, the Lib Dem’s core constituency. They vote largely on the basis of tuition fees. Miliband’s promise of a post-education tax only payable once a certain level of income is reached is supported by the National Union of Students (NUS) and most students themselves. It is a rather startling act of confidence, given Vince Cable made a speech supporting it weeks ago and it is still (some wobbles notwithstanding) expected to feature as official government policy. Civil liberties and Iraq are the two main reasons voters flocked to the Lib Dems from Labour, and continue to act as the main barriers to a resurgence in Labour support among the liberal middle-classes.

“With me, you won’t have to choose between whether to accept a reactionary assault on the welfare state in exchange for greater civil liberties. You can have both a commitment to equality and to liberty.”

This is the crux of Miliband’s argument. Lib Dem supporters may be getting what they want on civil liberties, but it has come at the cost of a radical and revolutionary assault on the welfare state. It is a powerful and effective attack. Most Lib Dem voters will deeply uncomfortable with the government’s economic approach, and feel it has little mandate to go for a one-term reduction plan which envisages such a fundamental change in the British economy. Miliband is trying to bring down the barriers to their defection. There is one thing tainting his argument, however: he wrote the manifesto on which Labour ran in the last election.

“To the 1.5 million people who supported Labour in 1997 but have since then switched to support the Lib Dems, and to those who are long-term Lib Dem supporters, I ask you to look again at Labour. If you join Labour you can come together with the emerging majority in the Labour party who want change that is real and lasting. If you join before 8 September you can vote to make that change in the leadership election.”

The rhetoric Miliband uses helps cement the impression he is on the road to victory. Labour supporters tend to read the Guardian, and most of his moves have taken place within its pages. The section on an “emerging majority” purposefully implies he is gathering momentum – an ethereal concept essential to any successful election campaign (hence why polls are banned while voting takes place on election day).

The encouragement for Lib Dems to join Labour before the leadership vote acts as a double incitement, encouraging them to grab a chance at making a difference, but it also serves to justify such a letter being written before a new Labour leader has even been picked. Much more importantly, it reveals that the letter is only superficially addressed to Lib Dems. The real target, of course, are Labour members. The message is: ‘look at the people I can bring in’. The implication is that Miliband is ideally placed to take on a Tory/Lib Dem coalition. He can talk Lib Dem language and capitalise on their disaffection to a greater extent than his competitors for the Labour leadership.

“Help build the society of equality, liberty and democracy that we all believe in, and stop the unfairness of this coalition. Leaving your party is the most honourable course when your party leadership leaves you.”

Miliband’s enjoyable ending to his letter comes not so much from its rhetorical impact, but from the fact that he is perpetuating the very same message which those on the left, and in the Lib Dems, used to shriek at Labour members during the Iraq war.

Will it work? Miliband’s pitch is hugely premature if it is genuinely directed at Lib Dem members. They will, at the very least, wait until the party conference before making any snap decisions. Even then, the party will only lose serious numbers after the autumn spending review. Most analysts expect the loss of support to be gradual, as the narrative of public sector job losses dominates the front pages over the years ahead and positions become polarised.

But the letter is really to Labour members, not Lib Dems. Even here, its impact will be marginal. Most Labour members already accept that Ed Miliband is the best candidate to attract Lib Dem voters. Whether they are sympathetic to his views on civil liberties outside of that fact is open to doubt. More importantly, they may believe that he can attract Lib Dem votes but not win a general election. On that basis, his brother is the stronger contender, both in presentation and due to his long stint at the Foreign Office. Ed Miliband’s incessant concentration on the Lib Dems is an attempt to avoid that issue.

There is also a problem with tone. The coalition will gradually lose its popularity, which is already on the wane. But the public enjoyed the cooperative tone of the coalition, and Miliband’s open and regular party political attacks go against the current trend. Ironically, the man who makes the most of his desire to break with the past is also failing to question its assumptions about the way that politics is conducted.