Tuition fees sketch: Carnage in the Commons

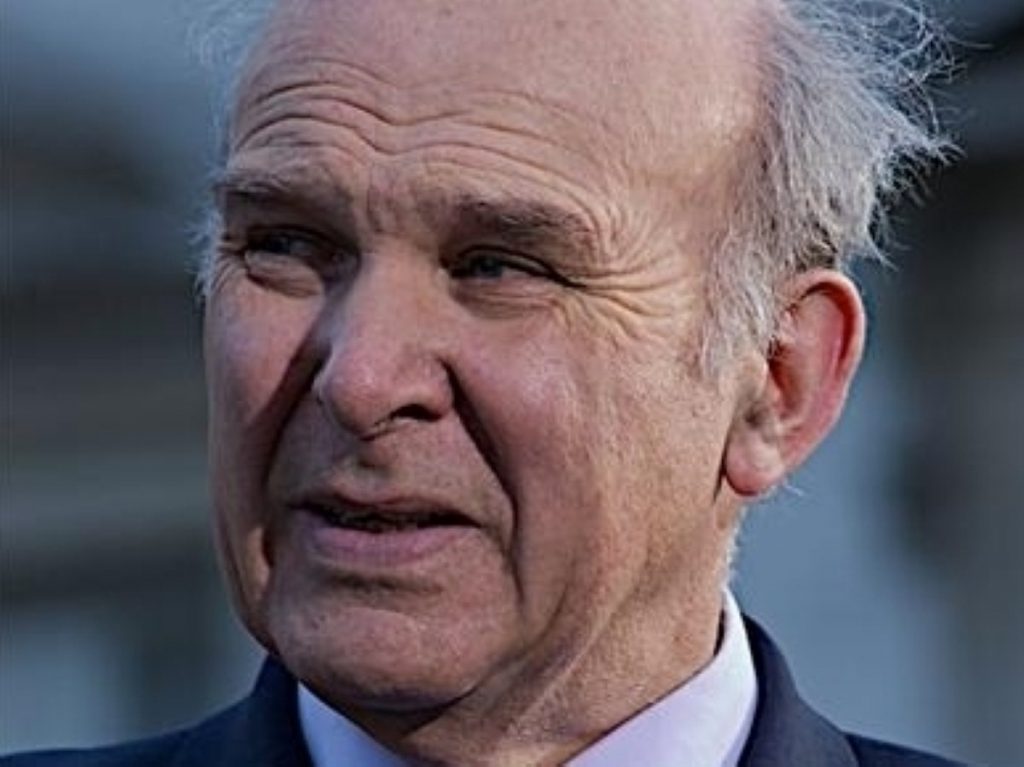

Vince Cable and co clung on grimly as the anger of a tumultuous, chaotic, unruly Commons swirled all around.

We’ve heard all the arguments before. This was just as well, for it was near impossible to hear Cable make a complete point uninterrupted by the shouting and jeers of the opposition. The volume in prime minister’s questions is always intense, but this was far worse. It was more sustained – and full of genuine fist-clenching bite. David Cameron and Nick Clegg flanked the business secretary, each interlocking their fingers and twitching nervously in the same way. Cable resembled an embattled aged relative being ambushed by the naggings of too many grandchildren. He struggled on, trying to appear serene. It didn’t work. When a minister addresses the Speaker as “secretary of state”, you know he’s rattled.

Part of the problem was he was constantly being interrupted by Bercow, who spent much of this lunch hour telling MPs to shut up. When this happens the minister sits down politely before resuming his speech. But it’s often unclear whether he actually needs to do so. Cable’s situation was summed up by the moments he spent in this pose – bent double, quavering, cowering, looking upwards desperately for some sort of guidance. It was a pitiable sight to look at, and perhaps a cruel point to make. But no one present could deny it summed up Cable’s position.

Worse still, the ex-saint was constantly being demanded to ‘give way’ – a form of consensual interrupting which MPs take great pleasure in. Labour’s appropriately red-faced Brian Donohoe was the most persistent offender, demanding to be given his say in his South Ayrshire accent roughly every two seconds. Eventually he had had enough, interrupting proceedings in a way John Bercow could not ignore. The Speaker was unsympathetic. “That is not a point of order, that is a point of frustration,” Bercow said, to laughter. Donohoe sat down thoughtfully – but only for a moment. “Will the right hon member give way?” he asked again.

It was the only funny moment in a grim first hour of this marathon debate. In the stranger’s gallery up above, a brief kerfuffle occurred as a few pesky students attempted to make their voices heard. The glass screen put in place to protect MPs meant the applause of other youngsters present barely filtered through, as dementor-like doorkeepers descended to bundle the miscreants away. The proceedings of the Commons continued uninterrupted. MPs barely noticed.

Down below, the Liberal Democrat benches were in a hellish form of collective agony. Over recent months they have become well-practised at looking vacant while in the chamber, blank expressions on their fixed faces as they let through this or that concession. Today was different. Abstainer Simon “get off the fence!” Hughes, the party’s deputy leader, sat forward intently, elbows on thighs. John Pugh was on the edge of his seat, sitting up primly with his arms folded. Julian Huppert and Duncan Hames, earnestly fiddling around with their phones, sat behind confirmed rebel John Leech, eyebrows permanently raised in a rictus of disbelief. This was that rare sight in the Commons since the election – Lib Dems not caring whether it looks as if they’re paying attention.

They did not like what they heard from John Denham, Labour’s shadow business secretary. He spoke at length in a powerful and effective speech, brushing aside most interventions but allowing one from the Lib Dems’ ex-higher education spokesman, Stephen Williams. Did Denham speak for or against Peter Mandelson’s planned £1 billion cuts for universities? “It wouldn’t have been unscathed,” Denham conceded, to Tory “ahs!” “But,” Denham added with a flourish, “it wouldn’t have been cut by 80%!”

By then the prime minister and Clegg had made their exit, Cameron not even bothering to remain in his seat until Cable had finished speaking. He slipped away, as prime ministers tend to do, behind the Speaker’s chair. But Clegg’s exit was more visible. He advanced in the other direction, towards where the Lib Dems used to sit. Labour MPs now occupying those benches jeered him, waving their order papers. The deputy prime minister acknowledged this barracking with a courteous – if somewhat supercilious – nod of the head, before presumably turning left and entering his whips’ office for a crisis update.

This explains why he missed Denham’s magnificent closing, a heartfelt appeal to undecided “ministers and backbenchers”. The words were not striking in themselves – “I do know what you’re going through – after you do it, you realise it wasn’t half as bad as you thought it would be”. Rather it was the hush with which his words were greeted that proved so stirring. After an hour of incessant heckling, the Commons fell silent once more as Labour MPs let Denham’s words sink in. It was, perhaps, the final calm before the storm.