PMQs sketch: Cameron comes close to losing it

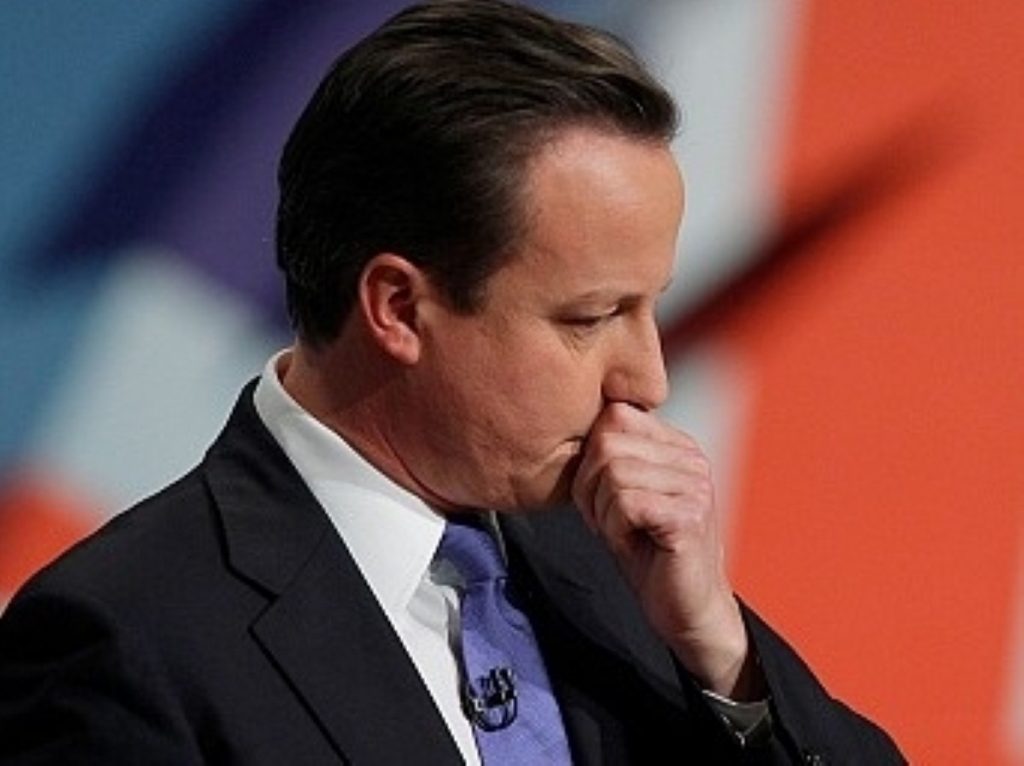

It was the moment David Cameron's carefully preserved statesmanlike image came close to falling apart.

Anyone who watches him regularly will knows that angry flashman alter-ego is never far from the surface. Today it seemed to almost overcome him.

The mockery began with his first word. As the prime minister told the Commons the usual summary of his appointments – "this morning I had ministerial meetings" etc– the laughter began. 'I'll bet you did' Labour MPs seemed to be saying. Cameron grudgingly allowed it to wash over him, smiling acceptingly as he sat down.

Ed Miliband started well, discarding his usual faux-innocent opener for a harsh attack demanding an "excuse" for this morning's GDP figures.

Cameron, beset by problems, tried to squeeze every bit of statesmanlike charisma he could but to little avail. Miliband responded with concise, logical questions. He grew tedious after a while and switched to an attack on Hunt, but he did so confidently, shifting his weight and pointing a damning finger at the media secretary.

Cameron wetly tried to press on with the economy, prompting angry shouts from the Labour benches. He deployed the usual line, that it was Labour which created the mess, and earning strong support from the Tory benches. If he was being perceptive, this would have been his most haunting moment. The benches behind him were so sick of being on the back foot they were resuscitated by a default attack.

The prime minister said he wouldn’t pre-judge the Leveson inquiry on the Hunt/BSkyB row. Cue 300 Labour thighs being slapped and a rabid back-and-forth motion on the opposition benches. "Leveson is responsible for many things but the prime minister's judgement is not one of them," Miliband said. It was a good line. Nick Clegg sat pensive by Cameron's side, sombre.

Cameron started wielding Leveson like a human shield, relying on his inquiry to buy time, crouching under his elderly frame. The prime minister laboured under the useful fiction that the judicial process has any chance of taking precedence over the political momentum of scandal.

His strongest moment came when he highlighted discrepancies in Miliband's position on Leveson, along with a stab for jumping on every political bandwagon. The Tory benches became excited and it knocked Miliband off course. He looked flustered and failed to get his sentence out, stuttering "totally… totally… totally" until Speaker John Bercow stepped in and saved him.

"Totally pathetic answer," he shouted, once he had regained his composure. His voice had taken on a ruinous schoolboy quality, an 'it's not fair' voice, like the geeky kid at the back of the class complaining about how the rugby player gets preferential treatment.

But then Cameron made a mistake, and slipped up on one of Westminster's oldest jokes. The media secretary had his "full support" he said. As one, Labour adopted a nasty smile, and started waving goodbye to Hunt.

It was at this point Cameron lost his cool. Miliband's delivered a good little line – "the shadow of sleaze hanging over this government" – and Cameron's response fell apart. He barked at the leader of the opposition, his face reddening with anger. For a couple of seconds he actually seemed on the verge of losing control. It was easiest the angriest we’ve seen him. At least Kinnock looked absurd out of over-confidence – this would have been a darker matter altogether. You could easily imagine an involuntary screech entering his voice, to be repeated endlessly on YouTube.

Whatever else it was: It was un-prime ministerial, and if Cameron has one major strength over his Miliband it is that he is more prime ministerial.

It was not the result of Miliband's performance, which was better on a technical level than it was on a human one. And it was not due to individual Labour MPs, whose attacks later in the session were soppy and weak, like being savaged by a wet towel. It was due to Labour as a whole, as a pack, smelling blood. They were enjoying themselves and with a couple of good lines from Miliband it was enough to tip the prime minister towards sacrificing his best qualities.

After the session ended Hunt stood up to make a statement. He was visibly shaken by events, drowning in the reality of your first proper media onslaught. He struggled to gain mastery over his body language, keeping hold of the lectern like a walking frame. His voice quivered as he told the Commons his special adviser, Adam Smith, who featured in yesterday's emails, had resigned.

Labour savaged him for that. "When posh boys are in trouble they sack their servants," Denis Skinner suggested. Hunt remained seemingly harmless. Smith is "a man of dignity", Hunt said meekly. He had the kind, sensitive eloquence of a man who sacrifices his underlings.

His response to Harman, who had a mediocre turn demanding his resignation, was disingenuous at best. He attacked the deputy Labour leader for failing to rise "above party politics" and, bafflingly, said he was "hugely disappointed" in her. He attempted a long citation of Labour's dalliances with the Murdoch empire, to a growing cacophony of hatred on the opposition benches. Ultimately, he suffered the peculiar indignity of having Bercow delicately tell him to address the matter at hand.

Can he survive? Stranger things have happened. Will he ever recover? Probably not.