Comment: A deal with the DUP could threaten the Northern Ireland peace process

By John Perrygrove

Much has already been written about the impact of a potential deal between Labour and the SNP after the general election. But could a deal between either the Conservatives or Labour with parties in Northern Ireland actually pose a far more significant threat to the future of the UK?

Historically the 18 constituencies of Northern Ireland have tended to matter little to the make-up of the UK Parliament. This could soon change, given the strong likelihood that neither the Labour or Conservative parties will gain enough seats to form a majority on May 7th. Other than the Conservative party, which polls locally at little more than 0.5%, none of the UK-wide parties have a presence in Ulster. Instead, a number of parties broadly organised along sectarian lines and reflecting Northern Ireland’s troubled political past compete for votes.

The Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) was traditionally the cross-class party for those who wish to continue Northern Ireland’s constitutional links with Great Britain. Until 1972 UUP MPs took the Conservative party whip. But their support base has been increasingly eroded by the more right wing Democratic Unionist Party (DUP). They instinctively support a number of Conservative party policies such as the planned EU referendum, but are also in favour of social programmes which would benefit their working class and agricultural base. For example, they are strong opponents of the so-called “bedroom tax”. Originally the only major party to oppose the Good Friday Agreement, which brought the first semblance of peace and security to Ulster, they now form part of the cross-community power sharing executive government working to implement it.

On the nationalist side of the spectrum Sinn Fein (SF) is the dominant left wing republican party supported by the Catholic working class. Its support base has expanded significantly since it embraced peace in the late 1990s at the expense of the traditionally dominant Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP), ostensibly a social democratic party with links to the Westminster Labour party. Both parties want a united Ireland although the SDLP have always rejected the use of violence as a means to that end. Sinn Fein also refuse to take their seats in the Commons.

Among the smaller cross-community parties, the Alliance Party draws its support mainly from middle-class professionals in the suburbs of Belfast and from newly arrived immigrants. Its leadership maintain it is the only major Northern Irish party which does not base its politics around the constitutional question. Alliance has strong links with the Liberal Democrats in Britain, although the party’s one MP in Westminster, Naomi Long, does not take the Liberal Democrat Whip.

Much to their consternation none of the Northern Ireland parties were included in the seven-way televised leaders’ debate that took place earlier this month. The DUP, who were the most visibly riled, argued that with eight MPs in the House of Commons they are a larger party than the Scottish Nationalists, Greens, Welsh Nationalists, and UKIP, all of whom were invited to take part. TV executives explained that their omission was because "the party systems in Northern Ireland and in Great Britain are different and our debates plan reflects that". In part this explanation highlights how distant, and complicated, Northern Irish politics often feels from that of the mainland UK. Northern Irish politicians were instead afforded the opportunity to debate separately on a programme broadcast locally.

It is almost certain that neither of the UK’s main political parties will win enough support next month to convert their votes into a majority of seats in the Commons. Throw into the mix a likely strong showing for the SNP and the probably presence of smaller parties – the greens, Plaid Cymru, UKIP and a much reduced Liberal Democrat showing – and post-election Westminster will be a complicated arena. This means that Northern Irish MPs may have influence in deciding the Westminster government in two ways. Firstly, Unionist MPs may be in a position to keep a government in power (as in the late 1990s, when John Major’s government came to rely UUP help to win crucial votes following the by-election defeats which crumbled his wafer thin majority). Secondly, Sinn Fein’s refusal to take up its seats potentially lowers the threshold required for a majority or to make a minority government stable. The five seats Sinn Fein won in 2010 lowered the threshold needed for a majority from 326 to 323.

Doing deals

The campaign in Northern Ireland is being dominated by the potential for agreements to be made – over whether a party might offer to support a minority government in a hung parliament; whether a deal between the two main unionist parties in four constituencies might produce unionist MPs; and whether the ailing Stormont house agreement currently deadlocked in the Northern Ireland Assembly might be rescued.

The DUP has already stated what its price would be for supporting a minority government in London. Party leader (and current Northern Ireland first minister) Peter Robinson has refused to put a number on it but it seems that more cash for Ulster from the Treasury is a priority for him. He also wants an end to the spare room subsidy in Northern Ireland and a commitment to maintaining UK defence spending at current levels. He has said that the DUP will work with either the Conservatives or Labour to get the deal it wants, although it has ruled out taking a formal role in a government. It has also ruled out entering into any arrangement that would benefit parties, like the Scottish National Party or Plaid Cymru, whose aim is to break up the United Kingdom. The Conservatives would seem to be the natural bedfellows of Northern Ireland unionism and the recent agreements of Westminster loans to Northern Ireland and the devolution of corporation tax rates to Belfast should be seen as early signs of the Tories reaching out to the DUP in anticipation of a hung parliament.

The SDLP, who currently have three seats in Parliament, has yet to say what it would seek in return for the support of however many MPs it returns to Westminster this time around but in 2010 it made a vague promise to “use any influence it had in a hung parliament to benefit the people of Northern Ireland and to counterbalance unionist demands”.

In four constituencies the DUP and the UUP have agreed to stand only one candidate in order to avoid splitting the vote and handing wins to nationalist parties. The Ulster Unionists have agreed to step aside in North Belfast and East Belfast and the DUP said it would not run candidates in either Fermanagh and South Tyrone (which in 2010 became the UK’s tightest marginal when Sinn Fein won by just four votes) or Newry and Armagh. The Alliance party described the unionist pact as anti-democratic and the SDLP described it as "a sectarian carve-up". The SDLP have rejected a similar offer of a deal by Sinn Fein. Sinn Fein said their proposed agreement would be about "progressive politics" but the SDLP said it "did not enter into sectarian pacts".

But whether unionist deals will hold together is not certain. Previous attempts to field just one candidate have failed, with deals breaking down, or discontented party members not willing to toe the line deciding to stand as independent candidates and creaming off crucial unionist votes.

In December 2014, the five main parties in the Northern Ireland Assembly reached broad agreement on a number of contentious issues that threatened the stability and effectiveness of the fragile Northern Ireland executive government. A key issue was welfare reform. As part of the so-called Stormont House Agreement, brokered alongside the British and Irish governments, a deal was struck to create a fund that would help welfare recipients who will lose money as a result of changes passed at Westminster but not yet implemented in Northern Ireland. However, on 9th March Sinn Fein suddenly withdrew its support for welfare reform, accusing the DUP of reneging on commitments to help the most vulnerable. The DUP in turn accused Sinn Féin of bad faith. Most commentators are scornful of Sinn Fein’s behaviour, and suggest that the U-turn on welfare provisions was ordered by Sinn Fein’s leadership in Dublin, who are eyeing elections to Ireland’s parliament in 2016 where they will be standing on an anti-austerity platform.

The row has stalled the entire deal, putting several other key plans at risk, including measures designed to reconcile communities with Northern Ireland’s violent past, as well as the implementation of corporation tax varying powers which Ulster’s business community deem crucial to Northern Ireland’s economic recovery. Also at risk is the power sharing government itself, which relies upon the trust and goodwill of both sides of the political divide for its very survival. Urgent talks have been ongoing in an attempt to salvage the deal; both the UK and Irish governments, as well as international partners have urged politicians to show leadership and work together to restore stability. But it may yet take the outcome of a highly unpredictable general election to decide the Agreement’s fate.

A threat to peace?

Knowing the extent to which Northern Ireland’s electoral results might impact upon the formation of the next government is rather difficult to predict, given how close a number of seats were in 2010, and that local complexities, often linked to sectarianism, mean that voting patterns do not always reflect a party’s performance in office. The Alliance Party’s sole seat in East Belfast, a wealthier unionist area, was lost by the DUP in 2010 after a local scandal. Sitting MP Naomi Long’s majority of only 1,500 will be hard to uphold if the DUP put resource into regaining its support there. Fermanagh & South Tyrone, with its four vote majority, is clearly up for grabs. And Belfast North, where all four parties do well, looks as though it could pass from DUP to Sinn Fein. The complexities are compounded by the lack of regular polling data for Northern Ireland as a whole, let alone at constituency level.

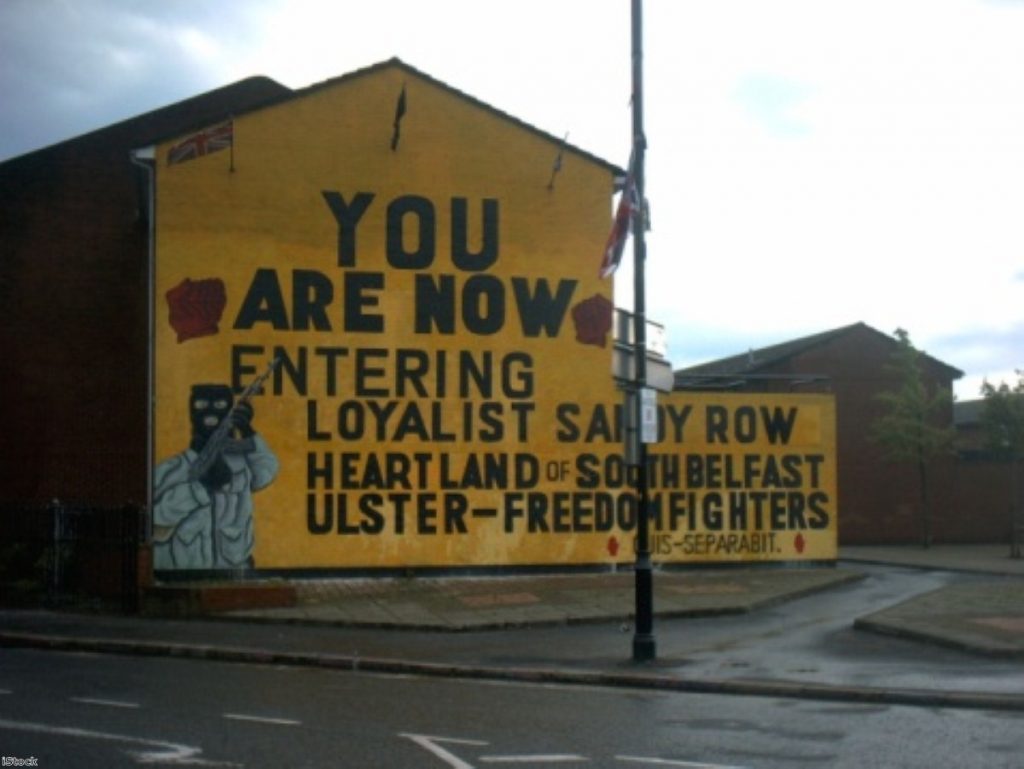

Not only might the preferences of Northern Ireland’s electorate affect a Westminster government, but the make-up of that new government could foreseeably have negative consequences for the future direction of the Northern Ireland peace process itself. For decades successive British governments have been able to present themselves as relatively neutral brokers in the peace process whose over-riding interest was bring peace to Northern Ireland rather than holding onto it for any economic or strategic reasons. A key reason why Sinn Fein was persuaded to give up violence and pursue peaceful political change means was their acceptance of the idea that the British government was not intent on keeping a presence in Northern Ireland at all costs and would even, in theory, facilitate an independence referendum if that was the democratic will of the population. But if a party in Westminster in May forms a government that relies upon Unionist parties in any form London’s ability to present itself as an impartial actor will be undermined. Efforts to continue to implement the tricky and more divisive elements of the continued peace process will be far harder if nationalist politicians (and the Irish government for that matter) suspect that the UK establishment is appeasing its new-found unionist allies.

Not since the end of the 19th century (when Charles Stewart Parnell’s bloc of 86 Irish nationalist MPs held the balance of power after the 1885 election) have Irish politicians of any colour potentially held such disproportionate clout in Westminster. The parties in Northern Ireland could make significant gains for their communities if they embark upon a course of wise deal making. The Westminster parties, who will be desperate to form a government, will need to consider whether doing so might prejudice ongoing peace and reconciliation in Ulster.

John Perrygrove is a political analyst focusing on the politics of Westminster and the UK's devolved administrations. He also advises on parliamentary business and procedure. He was previously a UK civil servant who specialised in foreign affairs, defence and national security policy. He has served as a private secretary to ministers in both the coalition government and the previous Labour administration.

The opinions in Politics.co.uk's Comment and Analysis section are those of the author and are no reflection of the views of the website or its owners.