By Pav Singh

When 8,000 citizens in the world's largest democracy were murdered in a government-orchestrated genocidal massacre in just four days, how was it possible for the guilty to evade justice? And to what extent does the West, and Britain in particular, need to look at its own complicity in this tragic affair?

On October 31st 1984, Indira Gandhi prepared for an unusually busy day of meetings scheduled with members of the British media, politicians and royalty.

The morning was to begin with a TV interview with the actor and dramatist, Peter Ustinov. In the afternoon she was due to host former British prime minister, James Callaghan, for tea followed in the evening with a private dinner with Her Royal Highness, Princess Anne, who was in India in her capacity as the president of Save the Children.

Elsewhere in New Delhi the England cricket team, led by its captain, David Gower, was landing at the airport for a hotly anticipated cricket series with India—one that would be played against a backdrop of unfolding violence, terror and disaster.

For the first of these appointments, Gandhi took a fateful stroll a short distance from her official residence to her office where Ustinov was waiting. As the unexpected sound of gunfire broke out, members of his crew initially mistook the sound for firecrackers. In actual fact Gandhi had been gunned down by two of her Sikh bodyguards.

In that instant, India, and the fate of one of its smallest but most prominent minorities, would change irrevocably.

Over the course of four horrific days, Delhi – and many other towns, cities and villages across India – was plunged into an orgy of premeditated violence of unspeakable brutality. The killings were on a scale not seen since the Partition of the subcontinent in August 1947 after the British had made their hurried departure, leaving behind the world’s largest mass migration of humanity and suffering on an unimaginable scale.

In November '84, the carnage was just as furious, but unlike '47 it was one-sided, carefully planned and executed with chilling precision and terrifying hatred whipped up, in part, by state-controlled TV and radio (where the slogan 'blood for blood!' was reportedly repeated again and again) and members of the then ruling Congress Party.

The minority Sikh community – one which had played a disproportionately large role in both the subcontinent's independence struggle and the Indian Army before and after '47 – was set upon in a manner that left one former MP, the Sikh historian Khushwant Singh, to state that "for the first time I understood what words like pogrom, holocaust and genocide really meant".

He wasn't wrong. Testimony after testimony of independent eyewitnesses, survivors and journalists attest to the premeditated, systematic targeting of Sikhs on the streets and in their homes. Entire neighbourhoods of Delhi, including ones within spitting distance of the nation's parliament and government buildings, were reduced to smouldering ashes.

Men, women and children were butchered, often burnt alive, with the complicity of local police. Women and girls were systematically raped, and many then murdered. Gangs were bussed in, armed, and often led without fear of arrest by local Congress politicians spurring the murderers on by directing them to houses that had been pre-marked in a manner reminiscent of Nazi-era Germany.

The killings have correctly been defined as genocidal in nature and, extraordinarily, exceeded the civilian death tolls of the recent conflict in Northern Ireland, Tiananmen Square and 9/11 combined. And yet, for thirty-three years the guilty have evaded justice, some even going on to attain senior positions in government and the police force. The survivors, however, have grown evermore weary with age, losing hope of ever gaining justice for their devastating losses of family members, businesses and homes.

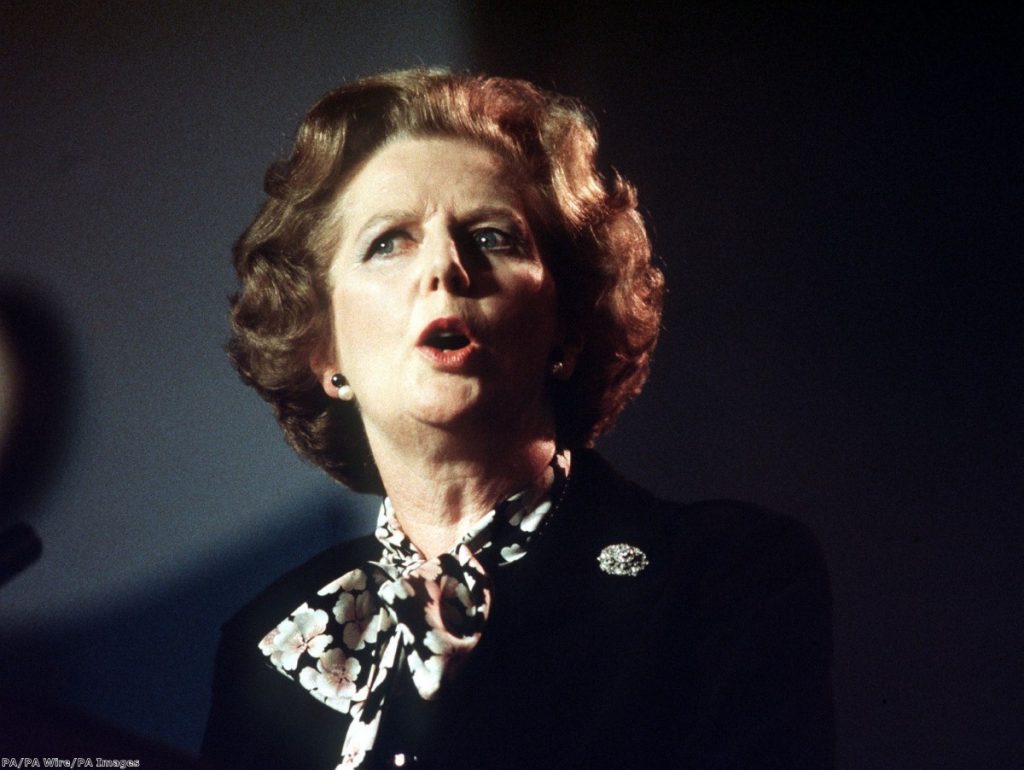

What was the reaction to this horrifying news in Britain? Following Gandhi's assassination words of sympathy were understandably expressed in parliament including by Margaret Thatcher and others in her government. But in the aftermath of the genocidal massacres, not a single mention was made in parliament of the thousands of innocent Sikh victims – despite the story being global news and making the front page headlines of Britain's broadsheets. As Princess Anne's personal protection officer recollected, the day before Gandhi's funeral people could hear the sound of violence emanating from beyond the walls of the British High Commission. There was no doubting that London knew what was happening in the heart of the world's largest democracy.

Recent declassified records from the National Archives reveal why the British government remained silent and the lengths to which the Thatcher administration was prepared to go to ensure that trading arrangements with India were not jeopardised – especially not by Sikhs protesting over the massacres in the wake of Gandhi's assassination. Trade trumped human rights.

Yet Thatcher's attitude towards Sikhs had not always been so cynical. In 1976, not long after becoming leader of the Opposition, she was chairing a shadow Cabinet meeting to discuss immigration policy when proceedings were interrupted by a bell. When she was told it was for a vote that was about to take place in the House of Commons on a motion to grant the exemption to turbaned Sikhs riding motorcycles, she stopped the meeting. What happened next was described by Michael Portillo, then a young researcher who would later on become one of her junior ministers:

"I must go," she said. "I am pledged to support them." One of the giants from the Heath cabinet, Lord Carrington, muttered something she didn't catch. Like a schoolboy, he was made to repeat it. "I said it was ironic that here we are devising how to keep people out of the country, while you are off to vote for the Sikhs." Silence. "It was a joke." She looked at the former defence secretary as though he were a piece of dirt. "Well, it wasn't very funny. These people fought for us in the war, Peter, fought for us in the war. Have you got it?" And off she flounced to record her vote.

Just weeks before Gandhi's assassination, Thatcher had narrowly escaped an attempt on her life by the IRA. Gandhi had sent her a supportive letter questioning how such a thing could happen in a democracy. Gandhi's death nineteen days later caused the British prime minister considerable consternation. Yet no objections were forthcoming when this important trading partner was the one inflicting mass violence on its own people.

Records at The National Archives show that on November 1st there was growing concern in the British government for a deal relating to Westland plc, a financially ailing British helicopter manufacturer that had received an order for twenty-seven W30 helicopters from India. The deal had had the backing of Gandhi and was due to be signed off on the day of the assassination. The Westland negotiations continued until a formal agreement for the acquisition of twenty-one W30 helicopters – financed by £65 million from the British aid budget – was finally signed in March 1986.

Four years later, Max Madden, the Labour MP for Bradford West, wanted to find out for himself about the issues that his Sikh constituents were raising with him by visiting the areas affected by the anti-Sikh genocidal massacres. Reporting back to parliament, he detailed the scale of abuses against Sikhs in Punjab before describing his visit to Delhi, where he visited 1,200 widows. He explained how they struggled to survive, living in pitiful conditions with no water or electricity and at risk of typhoid and cholera. One lady he met had lost eighteen members of her family:

"None of these people, the victims of murderous communalism, believe that what happened was spontaneous. The mobs were organised. They were led. The plan was to kill as many male Sikhs as possible, including boys and even babies."

Speaking on the government's behalf, Tim Sainsbury, the under-secretary of state for foreign and commonwealth affairs, responded in typical fashion—India was a "democratic country" with "an independent legal system" and a "vibrantly free press in which injustices can be and are exposed". Subsequent UK governments, Conservative, Labour and coalition, have not sought to challenge this stance and continue to use the mischaracterisation of the crimes as a 'riot'.

Thirty-three years on, India's justice system has been shown to have spectacularly failed the victims of '84. Police were found to be manipulating evidence in favour of the perpetrators from the start and failed to record the majority of the crimes. Much of the victim testimonies were overlooked by the official, often hopelessly flawed, inquiries, particularly in relation to the killing of children and cases of genocidal rape against women and girls.

The conspiracy to murder and then cover-up this crime against humanity reached all the way to the very top of the Congress Party and the Indian state. The true extent is only now coming to light. The Indian authorities have a lot to answer for. But so too do the British. For too long 1984 has remained India's guilty secret. Now it's time for the truth.

Pav Singh is the author of 1984: India's Guilty Secret – out now from Kashi House.

The opinions in politics.co.uk's Comment and Analysis section are those of the author and are no reflection of the views of the website or its owners.