By Tom Chivers

Here's something that should be more widely known: the evidence for a 'fertility cliff' – the idea that a woman's fertility drops off precipitously in her mid-30s – is actually pretty weak.

Your chances of getting pregnant each time you have sex does start to reduce. But even at the age of 40, around half of couples will get pregnant naturally within a year, if they're having regular sex. Most couples take months anyway and often couples who fail in the first year just need more time.

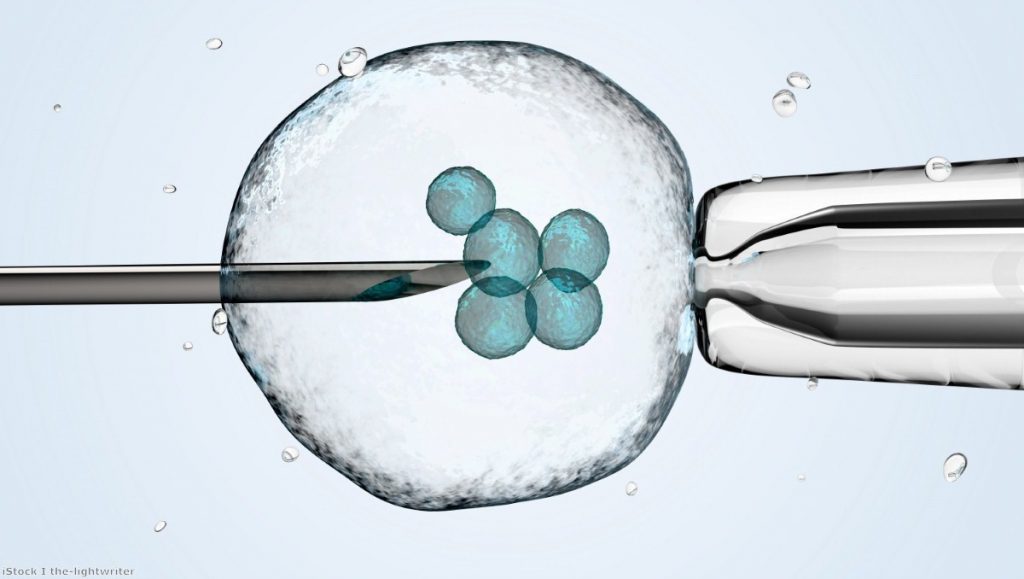

This is relevant because this week it was revealed by the BBC that several NHS Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) have stopped offering IVF, and others have reduced the service, to women over 34. Many more have dropped it for women over 39. Nice guidelines say that three cycles of IVF should be offered to women under 40 who have been trying to get pregnant for two years, and one cycle should be offered for women aged 40 to 42.

IVF isn't a magic cure-all. If you can't get pregnant naturally there's a good chance that you won't with IVF either, although I'm sure most of us know people who have. But it's not the case that IVF will suddenly become ineffective for women aged 35, any more than women aged 35 stop getting pregnant naturally.

Getting pregnant and having a child of your own is a vital part of life for many people. I know people who have adopted and they are adoring, happy parents who wouldn't change it for the world. But for some people, there is a psychological, and evolutionarily understandable, need for their child to be of their own flesh and blood. It makes complete sense for IVF to be available on the NHS, just like many other procedures which may not save lives but do improve them. These provide the "quality" in "quality-adjusted life years" (Qalys).

That said, there is a trade off to be decided here and it would be sensible to discuss it openly.

It costs money. Everything costs money. The NHS budget is now £152 billion a year, a total of 19% of all public spending and 23% of central government spending. The plan is to increase it to £172 billion by 2023. Paul Johnson of the Institute for Fiscal Studies says that that will be 38% of public service spending. Our ageing society will suck more and more money into its pensions and healthcare.

And every IVF cycle that the NHS provides is money that can't be spent on, say, a course of immunotherapy drugs for melanoma, or part of a new nuclear magnetic resonance imager, or even just a few weeks of a nurse's salary.

That's a truism. It's why Nice exists, to make those horrible trade-offs: this new cancer drug could save X lives, but it would cost Y pounds per life, and we would be able to save more lives – or, more accurately, save more Qalys – if we spent it on statins instead. So those X people have to die because the drug is too pricey.

We all hate that. The idea that there is a pound price on human life feels sacrilegious, which is why whenever Nice denies the use of some breast cancer drug there are outraged headlines. But there has to be. Spending the money on that breast cancer drug costs lives elsewhere.

That's why it’s a bit wearisome to read the health secretary, Matt Hancock, saying that the NHS CCGs' decision not to offer IVF for women over 34 is "unacceptable" and that decisions should be made on "clinical need" rather than a blanket ban. He knows as well as anyone that the CCGs have decided that money spent on IVF will have less of a positive effect than spending it on other areas of healthcare. Southampton City CCG was explicit about that, saying it had "taken into account the relative cost-effectiveness [of IVF] compared to other treatments that could be funded with the resources we have available".

There is not enough money to do everything the NHS would like to do. It's dishonest of any politician to say 'they should be doing more of this' without adding 'and therefore they should do less of that'. What would the health secretary like Southampton CCG to do less of, in order to provide more IVF for women in their late 30s? Paediatric surgery? Mental health support? Kidney transplants? Or just, you know, a little bit less of each, so that no one really notices, but there's enough scraped from all of them to pay for the IVF that's currently in the headlines, and then when there's not enough money for a dialysis machine in two years' time, they can cut it back the other way?

The thing is, all of these are legitimate options. You can perfectly reasonably argue that, say, a longer waiting time for children getting prostheses for missing limbs is a worthwhile trade-off for more couples getting IVF. But you have to first acknowledge the trade-off. A five-year-old knows that, sometimes, choosing option A means not having option B. Simply saying 'this bad thing is unacceptable, we should have less of the bad thing and more of the good thing' is, ironically enough, babyish.

Tom Chivers is a science writer. His first book, The Rationalists: AI and the geeks who want to save the world, will be published by Weidenfeld & Nicolson in 2019.

The opinions in politics.co.uk's Comment and Analysis section are those of the author and are no reflection of the views of the website or its owners.