By Ray Walsh

Preventing the spread of Covid-19 is essential to get the economy up and running again, and governments around the world are under pressure to find a solution quickly. This is leading to proposals for new technologies such as tracking apps, immunity passports and facial recognition cameras with built-in thermometers designed to single out people with a fever.

While these invasive surveillance technologies may be considered a necessary evil in the short term, privacy advocates recognise that there is urgent need for transparent sunset clauses to be declared alongside their deployment. After all, plenty of these apps have less-than-ideal privacy protections.

Failure to detail when these invasive technologies should be put to bed opens the door for them to remain even after the virus crisis is over. This creates the very real possibility that we will exit Covid-19 into a brave new world in which many of the basic freedoms we enjoyed in 2019 are gone, potentially forever.

In the UK, even before the coronavirus crisis, police forces were trialing the use of real-time facial recognition systems in public spaces. That technology was heavily criticised by privacy advocacy groups due to its potential to create an all-encompassing surveillance nexus.

Despite the determined opposition, early evidence suggested that the police would push on with the technology’s use, with a general feeling that it would only be a matter of time before those early trials spread across the rest of London, and then around the country.

That highly invasive real time biometric tracking is modelled directly on China's invasive facial recognition technology – systems that just a few years ago were considered the overreaching mechanisms of a totalitarian state.

With the desire to control the spread of Covid-19 now a priority, new tracking apps are being deployed that will allow consumers to know when they have been near someone with the virus and need to self-isolate. In the Chinese city of Hangzhou, the local government is already suggesting that those tracking systems should be made permanent to prepare for any potential second wave.

In India, a similar health tracking app called Aargoya Setu has been made compulsory for any citizen who wants to travel on domestic flights. This is yet another concerning sign of what might be heading to UK shores in the future.

For now, the government is claiming that any tracking apps for UK citizens would be voluntary. However, there seems to be a very real possibility that citizens may eventually be told that they need to be cleared by the app to qualify for international flights. If this is the case, it is easy to see why UK residents wanting to go on holiday – or who need to travel for business – may not consider the tracking app optional.

We can hope that once R reduces to within acceptable limits everything will suddenly go back to normal. Unfortunately, it seems possible that Western governments may instead take a leaf out of China's book. If, for example, it is claimed that keeping the R down it is necessary to continue using newly implemented tracking methods and technologies indefinitely, then we may not get the sunset clauses we need on the use of these invasive technologies.

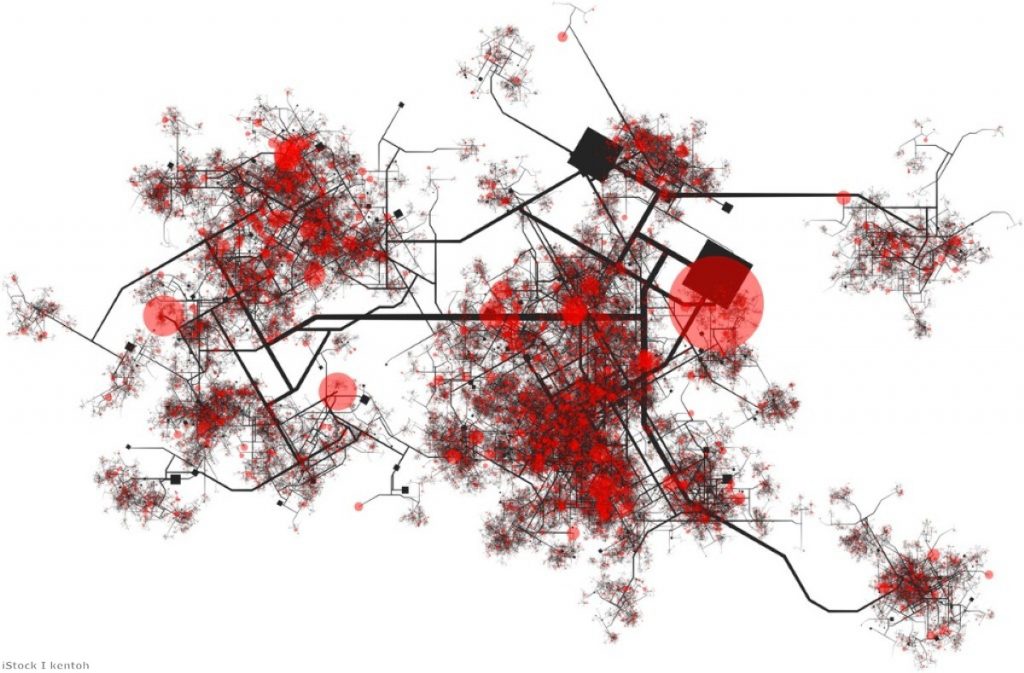

The result of this would be a radically altered society in which everyone's location is recorded constantly and where the right to private association is extinguished. In such a world, the government knows each and every journey you make, and every person you go near.

In China, where the government has already implemented a social credits system, this kind of tracking is already affecting society by changing the way that people intermingle. Fear of association is used as a powerful tool that magnifies social boundaries, and highlights the desire for people of different classes to segregate. A failure to do so may lead to discrimination, prejudice, and a loss of opportunity.

In the UK, this may seem like a distant nightmare, more akin to an episode of Black Mirror than anything we'd likely see on our shores. Yet if the past has anything to teach us, it is that the use of this kind of surveillance tech is manifesting into the West as quickly as a certain virus. With this in mind, it seems reasonable to question how this technology may restrict our future ability to associate or travel in privacy.

No-one can be sure when the coronavirus crisis will be declared officially over. We are dealing with the fear of a second wave and future pandemics. This, however, is being used as an unobjectionable reason for ongoing tracking, where governments appear to have found the silver bullet they need to leverage mass surveillance of their citizens. It must not become ‘the new normal’.

Ray Walsh is digital privacy expert at ProPrivacy.

The opinions in Politics.co.uk's Comment and Analysis section are those of the author and are no reflection of the views of the website or its owners.