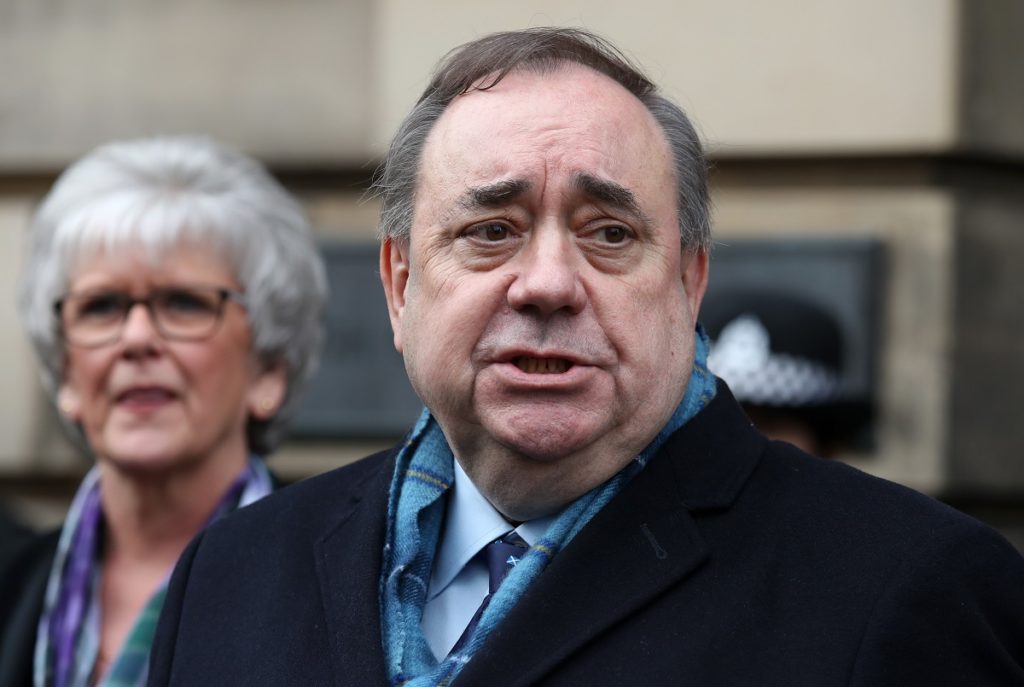

Former Scottish first minister Alex Salmond has launched a new party with the intention of forming a “supermajority” for independence in the Scottish parliament, together with the SNP and the Greens. His Alba party has momentum, but its strategy is to exploit a fault in Scotland’s largely proportional hybrid voting system. Alex Salmond’s latest venture exposes the need for electoral reform at Holyrood.

To someone with a limited knowledge of Scottish politics, Alba may sound like a development that will hurt the SNP in May’s Scottish election. But this is far from the case.

Under Holyrood’s Additional Member System (AMS), there are 73 single-member constituencies where the candidate with the most votes in each seat wins. Much like in the House of Commons, this constituency system leads to a mismatch between seats won and votes cast. As such, voters in Scotland get to cast an additional ballot, through which they choose a party. Within eight regional areas, these votes are tallied, and seats are allocated in a way that accounts for the number of constituencies already won by the party concerned. As such, parties that do well in the constituency ballot do not win many seats on the regional ballot.

In 2016, the SNP won 63 of the 129 seats in the Scottish Parliament (48.8%). The SNP achieved that by winning 46.5% of the constituency vote and 41.7% of the regional vote. Of the SNP’s 63 seats, 59 were constituency seats and four were regional.

Alex Salmond is now hoping to exploit Scotland’s current voting system by standing candidates only on the regional ballot. His explicit pitch to SNP voters is to support Alba on the regional ballot so to create an unrepresentative supermajority. As such pro-independence votes, which would not previously have counted in the regional ballot, given the likelihood that the SNP would win the constituency seats, could in effect now count double. Alba’s strategy is thus an overt attempt to game the system.

Ironically the distortion under this supposedly proportionate system could now be even worse than under a First Past the Post system.

Salmond’s dream scenario is for the SNP to retain their constituencies and for Alba to attract all of the SNP’s regional voters. Indeed if Alba managed to attract the 41.7% of the vote share that the SNP achieved on the regional list in 2016, then Alba and the SNP would together win 76% of the seats available at Holyrood, squeezing out other parties.

Despite him being cleared in a court of law, many SNP supporters may choose to avoid Salmond after the events of the last two years and his very public disagreements with former colleagues. Indeed Alex Salmond’s approval ratings among Scots dropped to minus 42% according to YouGov, little better than the minus 50% being experienced by Boris Johnson. However, if Salmond’s supermajority strategy can entice enough independence supporters, Alba has a real shot of winning seats in May.

Modelling by Ben Walker of the poll aggregator Britain Elects suggests that the Alba Party needs around 6% of the list vote to win seats this May. With the SNP currently polling at around 40% on the regional ballot, Alba would therefore need to attract the support of just over 1 in 6 SNP voters on the regional ballot to have a chance of entering Holyrood. The eventual distribution of seats will not be as unrepresentative as under Salmond’s ideal scenario, but it will still be present if Alba were to win a seat in each region.

There are no rules against Alba’s strategy, but it ultimately goes against the spirit of a system designed to create proportional outcomes. The Additional Member System, in its current form, marked the welcome introduction of Proportional Representation in Scotland, but change is now needed to avoid this gaming of the system and to ensure fairer outcomes.

Scotland could learn from Germany, which uses a similar mixed-member system. The main exception is that the size of the Bundestag is flexible with further MPs given to other parties if a party wins more constituencies than they would be entitled to purely on the regional vote. If such a modification were introduced here, Alba would still win representation if successful, but the number of total MSPs per party would more accurately reflect the regional vote share.

Scotland’s current Additional Member System has other faults too. Voters have little choice over individual candidates. Through regional lists, candidates are simply presented by parties to voters, with no opportunity for the electorate to allocate a preference to a specific candidate. The system also only ensures regional rather than national proportionality and creates two types of MSP (constituency and regional).

An alternative to tinkering with the Additional Member System would be to replace it with the Single Transferable Vote (STV), under which there would be multi-member constituencies with voters ranking candidates in order of preference. This would empower voters, end the two-vote MSP problem, and lead to largely proportional outcomes. STV is used for Scottish council elections and is recommended by the Electoral Reform Society.

Another fairer alternative would be an open list system under which voters would choose one party in their multi-member constituency and get a say in the ordering of candidates on their chosen party list. This variant is used by the likes of Denmark and Iceland in their elections and deploys national levelling to ensure complete party proportionality across the country. This is the approach advocated by Ballot Box Scotland.

The Additional Member System was designed to better match seats with votes, making it a fair alternative to Westminster’s unrepresentative First Past the Post system. However, 22 years later, its weaknesses are being intentionally exploited. Alex Salmond’s third act could falter but Alba’s intentions are a striking reminder that democracies should adapt to retain integrity. Scotland needs a new electoral system to provide fair and efficient proportional representation. Scottish democracy needs an upgrade.