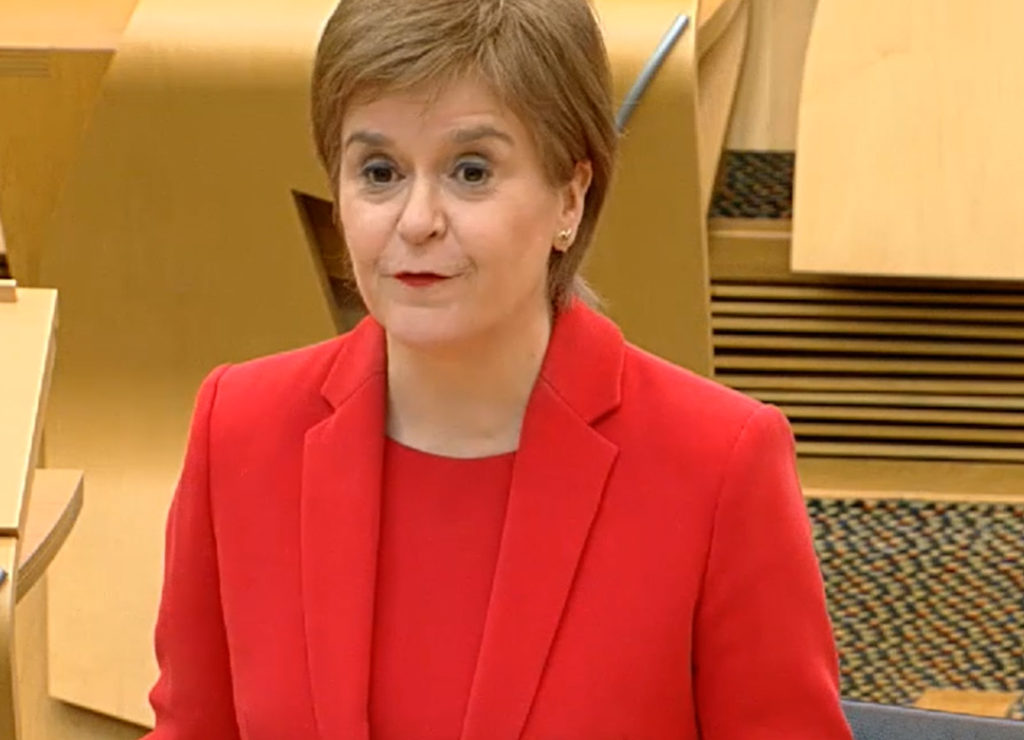

For all the talk of the SNP’s route to a majority closing up, the makeup of the Holyrood marginals will offer Sturgeon huge encouragement in the forthcoming Scottish Parliament elections.

Since Alex Salmond’s surprise entry into the 2021 Scottish election, much has been made of how the nature of the Scottish voting system – namely the ‘regional seats’ – might deny the SNP a majority.

There are 129 seats in the Scottish parliament, of which 73 – around 57% – are elected through the first-past-the-post ‘constituency vote’, the same system used for every seat in UK parliament elections.

However, the first-past-the-post system does not always allocate seats fairly, particularly for smaller parties, such that UKIP won 4 million votes in the 2015 General Election yet gained just one seat. So, with Scotland’s Additional Member System, the other 43% of seats – the ‘regional’ or ‘list’ seats – are allocated through a compensatory system based on the vote share in a particular regional area.

In the 2016 election this compensatory system was the SNP’s downfall. The Party won 42% of the regional vote but, because of their success in the constituencies, they only took 7% of the regional seats – four in total. This, combined with Alex Salmond’s party inevitably eating into the SNP’s regional vote share this year, means that Nicola Sturgeon cannot afford to rely on the regional seats for a majority as the SNP did in 2011.

But there is another route to a majority for Sturgeon – one that would represent an unprecedented feat in British electoral history. The SNP could win 65 of the 73 available constituency seats: an outright majority obtained through the constituency seats alone.

The system is simply not designed to produce such a thing; a constituency-only majority would require the SNP to win 89% of the available first-past-the-post seats. It’s never been done in devolved British elections, and rarely ever in recent European history using a comparable voting system – the last time being in Albania in 2001.

And yet, remarkably, it is a possibility in this election.

The SNP won 59 constituency seats in 2016, so to hit the 65 mark for a majority, the party needs a net gain of six. Simple though it sounds, that is a big ask with no margin for error. The SNP didn’t even come close to it in their historic 2011 win.

So what’s different about this election?

The state of play in Holyrood’s most marginal constituencies offers some indication. As shown in the graphs below, only one of the 10 most marginal constituencies in Scotland is currently held by the SNP. It is thus the Conservative and Labour parties who are sitting on the most vulnerable electoral assets.

If just six of these marginal seats turn yellow, then the SNP will be in a strong position for a constituency-only majority.

Which seats can the SNP gain?

In political terms, the last election at Holyrood was held in a different political epoch. That election was two Prime Ministers ago, and prior to the 2016 Brexit referendum.

So, to get a sense as to how the SNP may fare in these marginal seats in 2021, it’s helpful to look at how the same areas have voted in the subsequent 2017 and 2019 General Elections. This is not an exact science, as Westminster and Holyrood constituencies are drawn up slightly differently, but it still highlights some significant patterns.

Since the last Scottish election, the SNP have won in five equivalent UK parliament constituencies, which they didn’t win in the last Holyrood elections in 2016:

Labour-held Dumbarton, a strong pro-independence area, and Tory-held Edinburgh Central, where the popular Ruth Davidson is standing down, both seem winnable targets for the SNP this year. The party will also be hopeful of securing Eastwood, Ayr and East Lothian, all three of which flipped back to yellow in the 2019 General Election.

Labour-held Dumbarton, a strong pro-independence area, and Tory-held Edinburgh Central, where the popular Ruth Davidson is standing down, both seem winnable targets for the SNP this year. The party will also be hopeful of securing Eastwood, Ayr and East Lothian, all three of which flipped back to yellow in the 2019 General Election.

However, even if the SNP win all five of these and hold onto all of their current seats, they would still be one short of a constituency-only majority.

The hardest task for the SNP will be flipping the one further seat they need. This would be the one which they haven’t won in any of the previous three Holyrood and Westminster elections:

Edinburgh Southern and Dumfriesshire would appear less likely targets for the SNP, but keep your eyes on the results in Aberdeenshire West and Edinburgh Western, both of which the SNP won in 2011. Voting in these seats has fluctuated widely in the past decade, and if either flip to yellow this year, that will be a troubling omen for the SNP’s rivals.

With a potential electoral improvement for the SNP now, compared to the 2016 result, the SNP gaining the six additional seats they need seems more than possible. But that’s only half of the task.

Can the SNP keep hold of all of their seats?

Although nine of the top ten most marginal constituencies in Scotland are held by the SNPs opponents, the party will still need to hold all of the constituencies that it won in 2016.

Two danger zones for the SNP are Moray and Caithness and Sutherland & Ross; though neither majority was particularly thin in 2016, the SNP have performed poorly in both areas in more recent general elections.

Nevertheless, there is good news for the SNP in both cases. Tory leader Douglas Ross, who claimed SNP scalps in both of the previous Westminster elections in Moray, will not be challenging the seat this time. Meanwhile, the challenge in Caithness, Sutherland and Ross comes from the Liberal Democrats – whose current constituency polling average is almost two points down from their 2016 result.

The SNP have clear reasons to be optimistic about the constituency vote this year. Their current constituency polling is 4% higher than their actual result in the last election. To win an outright majority at Holyrood based on the constituencies alone, all they need is 4,628 votes to change across six marginal seats.

Although the SNP polling has fluctuated in recent months during the Salmond inquiry, the party still has a genuine chance of making British electoral history by winning a majority without the need for a single list seat. If they did so, they would send a signal to Westminster that Boris Johnson may find harder to ignore.