Before entering the world of politics, I had a 25-year career in the NHS, latterly leading rare cancer nursing services at the Royal Marsden Hospital in London.

Cancer patients’ immune response is very often affected by the chemotherapy used to treat their disease, so the management and control of infection is a central concern in cancer care. This is particularly true for bone marrow and stem cell transplantation where the immune system is completely ablated and the person is placed in protective isolation to minimise the risk of infection.

While infection control is important, the principles employed are reasonably straight forward. Firstly, non-pharmaceutical interventions are put in place. This includes appropriate isolation measures to create a buffer between infectious sources and those at risk, thorough hygiene practices, and the use of personal protective equipment (PPE). Secondly, it is essential to deliver preventative immune therapies like vaccines and to provide drug and other supportive therapies as necessary. Finally, there is a need to employ robust surveillance of the developing infection within and outside the host. This is largely achieved though clinical observation of temperature, pulse blood pressure and the like, but it also includes surveillance testing and screening of the in-scope population.

Whilst there may be some further nuanced considerations that is effectively it.

The important point is that each of these three strands are interdependent and intrinsically linked, none are optional, let one fall and they can all fail. Sadly, that is where we find ourselves with the current UK government approach to the pandemic.

Specifically, there has been a wholesale abandonment of non-pharmaceutical interventions, an overreliance on mRNA vaccination and a disturbingly cavalier approach to testing and therefore epidemiological and genomic surveillance.

So, imagine that the UK is the patient, and the government is the responsible physician. For the physician to make the informed decisions they must have access to accurate clinical data like ‘obs’, blood tests, hydration, appetite etc. This information is vital because without accurate clinical data the physician would have to make decisions based on guesswork.

Now imagine you are the patient, and it is your physician that is making decisions about your health care based on guesswork. I’m certain such an approach would not inspire much confidence in your chances of being treated successfully.

Well, that is precisely why I have consistently raised concerns about the UK’s approach to testing since the early days of the pandemic. Yet while it seems things are lurching from bad to worse, there is some hope on the horizon, but only if the government gets its house in order and rallies behind the UK domestic diagnostics sector.

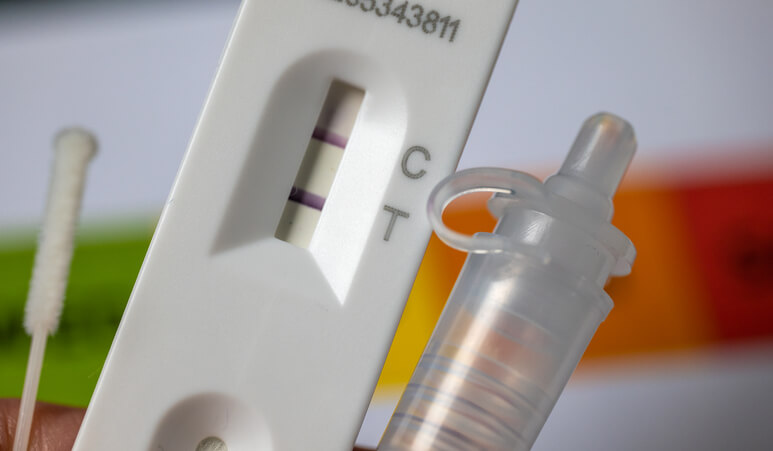

Since Matt Hancock toured the TV and radio stations preaching the near infallibility of lateral flow tests in late 2020, there has been growing concern about the quality of imported lateral flow devices the government procured at a cost of £3.7bn.

I first raised concerns set out in the British Medical Journal of this “unevaluated, underdesigned, and costly mess” with Dame Jenny Harries in November 2020 and I have been a determined thorn in the government’s side over their mass testing strategy ever since. Given the importance I place in clinical data you would be forgiven for wondering why? Well, it all comes down to the quality of data.

Accurate testing ensures people can confidently be instructed to self-isolate, and those not infectious can go about their business reassured that they do not currently pose a risk to others. It also means that those who test positive can be subjected to further viral screening. This allows lab staff to assess the genomic profile of the virus and identify emerging variants, where they are appearing and how the virus is spreading through the population.

All of this matters and is fundamental to a successful strategy. But what if the tests are not as reliable as Matt Hancock’s touted 95%-plus accuracy and specificity? What if they are nowhere near as reliable as that?

Unfortunately, that is exactly what was established by the government’s own Liverpool evaluation. The evaluation demonstrated that the imported Innova device only identified 40% of infectious subjects and missed 30% of those considered to be most infectious. Furthermore these same devices were subject to the most serious class 1 recall by the US FDA . However, the government have not only persisted with these tests, but they have done so in such a way that gives them an unfair advantage over the domestic diagnostic sector.

And there is a serious public health concern here. I’m not against mass testing per se, but misplaced confidence in underperforming tests may have amplified infection rates rather than suppressing them.

The UK government must urgently review their validation approach for superior UK manufactured lateral flow devices. They must show the same confidence the rest of the world has for emerging rapid artificial intelligence Covid tests.

Covid is part of our new reality, and it is incumbent on government to develop a resilient and accurate testing strategy that keeps us safe and secures domestic innovation, industry and employment into the future.

References

https://www.bmj.com/content/371/bmj.m4436%20

https://www.bmj.com/content/374/

https://www.bmj.com/content/373/bmj.n1514%20

https://www.bmj.com/content/371/bmj.m4436

https://www.bmj.com/content/374/bmj.n1637/article-info

https://www.bmj.com/content/373/bmj.n1514

https://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2021/910/contents/made

https://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2021/910/pdfs/uksiem_20210910_en.pdf