Just last month the prime minister’s spokesman claimed that there were “no plans” to introduce mandates.

However, during last Wednesday’s address in which the government announced both the rollout of Plan B Covid restrictions, and an expansion in the programme, the prime minister sparked controversy by suggesting the UK ought to have a “national conversation” regarding mandatory to prevent further lockdowns.

Where we are now?

Johnson’s move towards even considering compulsory vaccination marks a major shift in tone, and senior opposition figures including Greater Manchester Mayor Andy Burnham have slammed the idea.

Health secretary Sajid Javid is on the record as strongly opposing mandatory vaccines, telling BBC Radio 4’s Today programme just days ago that the practice was “unethical”, and arguing that it “wouldn’t work” “at a practical level”.

Javid said, “If you ask me about universal mandatory – as some countries in Europe have said that they will do – at a practical level I just don’t think it would work because getting vaccinated should be a positive decision”.

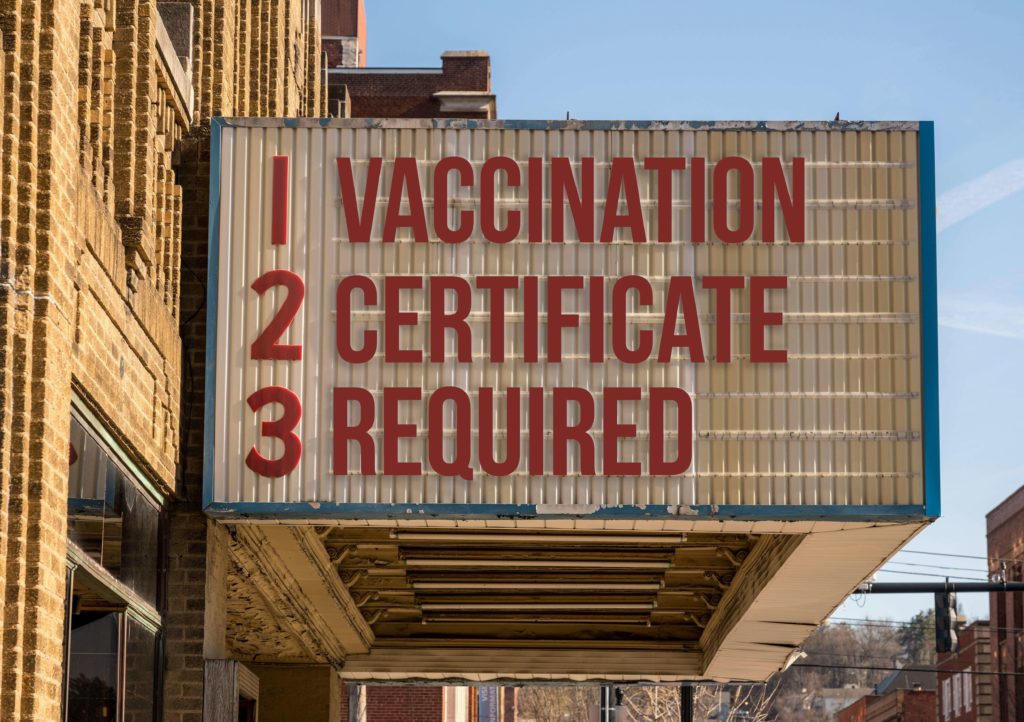

The government does though make an exception for health and care staff, given that they work in a “high-risk” environment. Since 11 November all care home staff have been required to show proof of a or medical exemption to continue to work.

Now the government plans to make vaccines compulsory for NHS England staff that have face to face contact with patients. The government will publish an impact assessment of the policy, and MPs will then vote on whether to introduce it. If approved by Parliament, the rule will come into effect 12 weeks after the vote, which the government aims to be by 1 April.

While there are no plans to make covid vaccinations mandatory for the rest of the population, the UK is not without its own history of compulsory for .

The UK’s Act of 1853 made it legal to issue fines to all parents who failed to vaccinate their children against smallpox within 3 months of birth, resulting in two-thirds of babies being inoculated against the deadly disease by the 1860s, slashing smallpox mortality rates.

The UK’s compulsory smallpox laws were scrapped in 1947. Instead public health policy moved towards optional , with the authorities favouring education and persuasion to underpin uptake.

Compulsory vaccines: Try the Continent…

In Germany, compulsory covid vaccinations are set to be debated in parliament this month, and could well become law by February. Allied to that, a German “lockdown for the unvaccinated” is set to be rolled out, in which people without a will be refused entry to “non-essential” shops and events, unless they can evidence a recent recovery from the virus.

“Culture and leisure nationwide will be open only to those who have been vaccinated or recovered,” outgoing Chancellor Angela Merkel said on 2 December.

Last week Austria became the first western nation to impose compulsory , with the plan again set to be introduced from 1 February 2022.

Greece is set to make a obligatory for people over 60.

Although member states maintain control over their own , the chief of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen said last Wednesday that the European Union ought to “think about mandatory ” against Covid-19.

She argued that it was “understandable and appropriate to lead this discussion now,” given that a third of the EU’s 450 million citizens remain unvaccinated.

What’s the case for compulsory jabs?

It almost goes without saying that compelling people to receive vaccines increases uptake, and reduces the overall rate of illness and death.

Where the flu is concerned, one study reviewed in the Lancet concluded that patients in hospitals where doctors and nurses had high rates of flu had mortality rates of around 13.6%, versus rates of around 22.4% where workers’ rates were lower.

The argument is made that mandating jabs is an act of social responsibility. It ensures that people reduce the risk that both themselves, and those they come into contact with, are likely to suffer from . Covid vaccines such as the Pfizer, AstraZeneca or that have 90-95% efficacy at preventing jabbed individuals from getting ill, are also likely to be effective to a degree at halting the virus from spreading.

Alberto Giubilini, a senior research fellow at the Oxford Uehiro Centre for Practical Ethics, argued that as “Mandatory seatbelt policies have proven very successful in reducing deaths from car accidents, and are now widely endorsed despite the (very small) risks that seatbelts entail. We [now] should see vaccines as seatbelts against COVID-19.”

Why many feel mandates are a step too far…..

While more people being jabbed usually means more people in better health, is it really wise to compel people on such a sensitive question?

If mandatory Covid vaccinations are green-lighted for the sake of health, why not consider such tough tactics to tackle other health issues? Why not implement ever-harsher measures against products such as cigarettes, alcohol and junk food, factors that contribute to cancer, heart disease and other illnesses which place more pressure on the NHS than Covid?

For those, who feel they lack , and worry about , compulsion represents too great an encroachment of state power.

In Brazil attempts at compulsory have even sparked violent riots, and it is thought such policies have in fact spurred on anti- movements online and across the world. Many experts argue that compulsion can increase distrust of medical authorities, as people are threatened with often harsh legal action if they refuse inoculation, which can lead to resentment and an openness to conspiracy theories as they perceive themselves pushed into a corner rather than worthy of persuasion and educational debate.

It is also true that compulsion is routinely used as a tool of repression in authoritarian regimes such as China- which is hardly great PR for the initiative in Britain and other liberal democracies.

NGO Human Rights Watch has highlighted that a “frenzy” of forced vaccinations began in China during July after President Xi Jinping announced the target of vaccinating 80 per cent of the country’s 1.4 billion population by 31 October. This led to an indirect mandate as officials were given quotas to fulfil.

Unvaccinated people in the cities of Xiaochang and Chongqing have complained of harassing phone calls and home visits from local officials. In Nanchang, the government offered to pay people who reported on their unvaccinated neighbours. Local authorities have also detained and questioned people who have criticised forced vaccinations.

While such harsh measures are unlikely to feature amongst Boris Johnson’s musings, for some they are a stark sign that mandates are often not the feature of a free society.

Mamta Murthi, the World Bank’s Vice President for Human Development, has also warned how it “is absolutely unacceptable, that a large part of the world remains unvaccinated”, emphasising that this is a “danger to all of us” given that t is more likely that new, dangerous variants will emerge if the developing world is not prioritised. Why not focus on ramping up global jab efforts rather to allow more vulnerable people across the world a choice, rather than forcing a few more thousand Brits to get their jabs?

These suggestions also beg the question of whether it would even be worth the political hassle to mandate jabs in the UK, given that it already has one of the highest COVID-19 uptake rates in the world, with 81% of all people over 12 years old having been double-jabbed, with all over-18s set to be offered the jab by 2022.

Rebels with a cause?

With upwards of seventy MPs set to rebel over tomorrow’s vote on Plan B restrictions, many city concerns over liberty and autonomy, it seems unlikely that the government would easily push through a mandate.

While tomorrow’s restrictions have Labour’s backing, Sir Keir Starmer-who has already opposed mandatory vaccines for NHS staff- and an even chunkier Tory rebellion than Tuesday’s forecast could easily stamp out such plans. However, given the appetite of many governments for compulsion, it is not impossible that compulsory moves up the policy agenda in the UK too.