MPs: Hybrid embryo ban ‘will harm science’

MPs have urged the government not to ban hybrid human-animal embryos, warning current proposals are too prohibitive and could compromise the UK’s position in the scientific community.

The Commons’ science committee says research into hybrid embryos should be allowed under licence, following scrutiny from the Human and Embryology Authority, and scientists should be allowed to continue with existing research practices, which are “essential tools in understanding diseases”.

In December the government published a white paper proposing a ban on the creation of part animal, part human embryos. This followed a consultation, in which the majority of respondents expressed unease with the practice.

However, the committee claim the consultation was “deeply flawed”. Liberal Democrat MP and committee chairman Phil Willis said that many of the groups opposed to the research, oppose any study of embryos. Of the 300 groups involved in the consultation, 277 were opposed to the creation of hybrid embryos.

The committee called on the government to remove the ban from the forthcoming draft fertility bill, to be published May 8th, which will overhaul many of the fertility restrictions.

It concluded: “We fully appreciate the concerns of those who oppose research into hybrid and chimera embryos – or indeed any human embryos – on moral and ethical grounds, but we feel that it is in the interests of science, the public and the UK that the current applications by King’s College London and Newcastle University should be considered by the HFEA promptly and with due process.”

“This is a test of the government’s commitment to science,” added Mr Willis.

Nevertheless, the Department of Health has defended the ban and its support for science. It said: “We have made clear our support for embryo research in the advance of science and medicine and our aim to maintain the United Kingdom’s position at the forefront of this technology,

“Whilst we have proposed an initial ban in general terms, we recognise that there may be potential benefits from such research and are certainly not closing the door to it.”

The Royal Society’s stem cell working group chair Sir Richard Gardner argued scientific progress must not be “hampered by heavy-handed legislation”.

“The technique to create human-animal cytoplasmic hybrids, as a potentially valuable way to overcome the shortage of human eggs for medical research, has only emerged within the past five years,” he said.

“We do not know what possibilities might emerge in the next five years so it is vital that new legislation can accommodate scientific breakthroughs.”

More than 220 medical charities and patients’ groups have co-signed a letter to the prime minister in support of the research.

Scientists claim the research could help develop new treatments for Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s and cystic fibrosis, and animal-human embryos could help them understand the molecular minutiae behind the conditions.

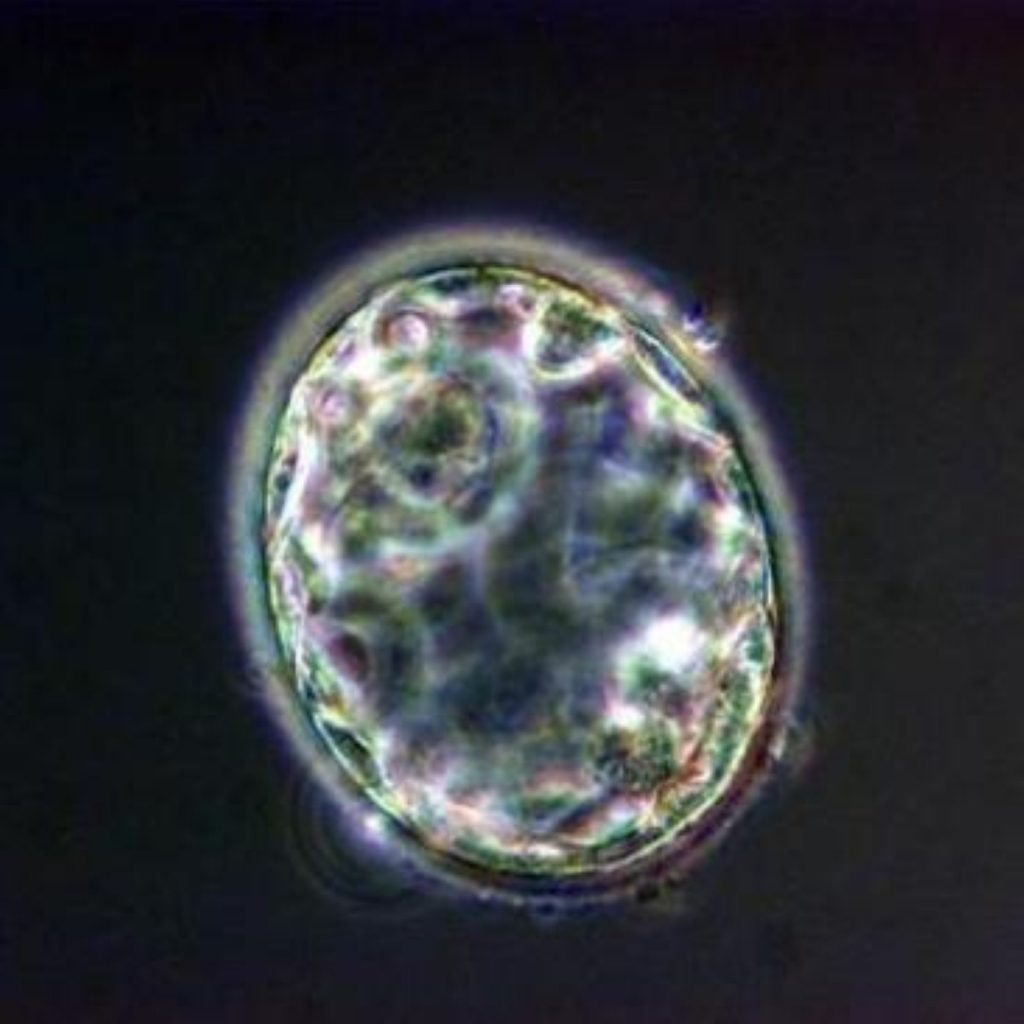

To create the hybrid embryos, scientists take human DNA and insert it into an empty egg from a cow or rabbit. Stimulation with a shot of electricity causes the two cells to fuse, creating an embryo which is 99.9 per cent human. Stem cells can then be taken from the embryo and used to grow tissues for research.