Baha Mousa inquiry finds ‘gratuitous’ violence led to innocent man’s death

By Alex Stevenson Follow @alex__stevenson

The September 2003 death of an innocent Iraqi man at the hands of British soldiers is a "very great stain on the reputation of the Army", the inquiry into his death has concluded.

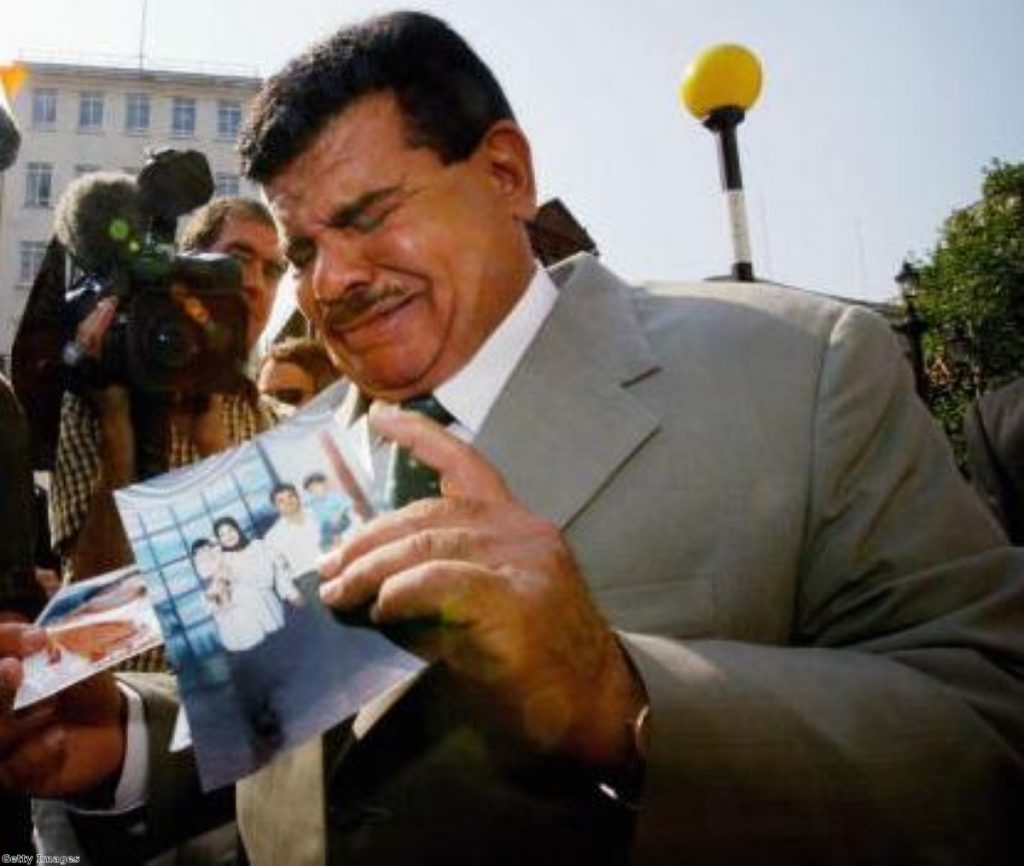

Twenty-six-year-old hotel receptionist Baha Mousa was found dead after two days of detention in which he was hooded and placed in stress positions, before being violently assaulted.

After two years probing the circumstances surrounding the death, Sir William Gage's inquiry could not find a single cause of death for Mr Mousa.

He was made vulnerable by a number of factors including exhaustion, fear and multiple injuries during his 36-hour captivity, but "the trigger for his death was a violent assault, consisting of punches, being thrown across the room and possibly kicks". This, combined with an "unsafe method of restraint", led to his death.

Speaking to the Commons, defence secretary Liam Fox said there could be "no excuses" for the events.

He refused to adopt one of the inquiry's recommendations on a blanket ban on certain non-physical interrogation techniques, however.

Mr Mousa was wrongly suspected by UK soldiers of being an insurgent who had murdered a popular officer, but Sir William Gage's inquiry did not offer excuses for those responsible.

He concluded that the events which led to Mr Mousa's death "constituted an appalling episode of serious, gratuitous violence on civilians which resulted in the death of one man and injuries to others".

Although the inquiry found that the incident was not a 'one-off' event, its 1,300-page report did not find an "entrenched culture of violence" in the battlegroup responsible for the 26-year-old receptionist's brutal death, 1 Queen's Lancashire Regiment.

Four soldiers are singled out as bearing a "heavy responsibility" for Mr Mousa's death.

But the inquiry concluded the MoD's "corporate failure" was partly to blame, as there were no formal guidelines in place on the interrogation of prisoners of war.

The inquiry found that the soldier responsible for the final assault, Corporal Donald Payne, had "devised" a means of assaulting the detainees known as the 'choir'.

"It consisted of Payne punching or kicking each detainee in sequence, causing each to emit a groan or other sign of distress," Sir William said. Cpl Payne was supposed to be supervising the detainees' welfare.

In 2006 Cpl Payne became the first member of the British armed forces to be convicted of war crimes after pleading guilty to inhumanely treating civilians. His six co-defendants were all cleared at the court martial.

Other, more senior officers, were also criticised. Lieutenant Colonel Jorge Mendonca did not know about Mr Mousa's detention, but the inquiry concluded that he "ought to have known what was going on".

Further criminal proceedings against key individuals involved in the case remain possible.

"This report does not mean that our investigations of mistreatment of detainees are over," Dr Fox said.

"The evidence from the inquiry will now be reviewed to see whether more can be done to bring those responsible to justice."

The Iraq Historic Allegations Team is revealing evidence of "some concern", the defence secretary noted. Any cases will be referred to the director of service prosecutions.

The "grave and shameful events", as the inquiry's report described them, were triggered by "violent and cowardly abuse and assaults by British servicemen whose job it was to guard him and treat him humanely".

The inquiry has submitted 73 recommendations to the MoD, including that it should retain its current absolute prohibition on the use of hoods on captured personnel. Perhaps the most sweeping is recommendation 65, which calls for the term 'conditioning' to be abandoned "because of its dangerous ambiguity".

Dr Fox told MPs: "The recommendation that we institute a blanket ban during tactical questioning on the use of certain verbal and non-physical techniques I am afraid I cannot accept."

He highlighted the difficult conditions faced by UK soldiers in Iraq at the time, but acknowledged that the "vast majority" of armed forces facing those challenges did not behave badly.

"If any serviceman or woman, no matter the colour of uniform they wear, is found to have betrayed the values this country stands for and the standards we hold dear, they will be held to account," he told MPs.

"Ultimately, whatever the circumstances, the rules or regulations people know the difference between right or wrong."

Shadow defence secretary Jim Murphy, whose Labour government was in power in 2003, said it was "unacceptable" that techniques banned by the UK government and by the Geneva Conventions should have been used.

"As we approach the tenth anniversary of 9/11 it is more important than ever to remind ourselves that our values separate us from our enemies," he commented.

"Our strength relies as much on the standards and ethics we uphold and pride ourselves on as it does firepower. If they are compromised so is the ability of our armed forces to act on the world stage."

Civil liberties group Liberty suggested that last week's 'leak' which suggested the report would conclude entrenched bad practice in the Army was starting to look like an attempt to put a positive spin on the scandal.

"We vividly remember just how strenuously some senior officials, lawyers and former ministers resisted the creation of this public inquiry into such appalling human rights abuse," director Shami Chakrabarti said.

"They should all search their consciences about how they allowed the five inhuman interrogation practices to be deemed acceptable."